The subject of plant growth regulators (or PGRs) comes up regularly in discussions of houseplants, and particularly tradescantias. You might notice the term mentioned in conversations about how to identify different cultivars, or about buying plants from shops.

This article will be an FAQ, covering (hopefully) any question you might want to ask about PGRs. The article is illustrated with photos from my own experiment, with the full procedure described at the end. Use these handy links to skip to the questions you’re interested in.

- What are plant growth regulators?

- What do plant growth regulators do?

- Why are plant growth regulators used?

- Are growth regulators harmful to plants?

- Are plant growth regulators a scam?

- How do I tell if a plant has been treated with growth regulators?

- How do I get rid of plant growth regulators?

- Can I use plant growth regulators at home?

- Details of the experiment

What are plant growth regulators?

Plant growth regulators are chemical treatments which affect the way plants grow.

Plants don’t have a nervous system, so they use chemical signals to send messages between different structures and control what they do. There are lots of different compounds which send lots of different messages. They’re involved in every part of a plant’s life cycle, from telling seeds when to germinate, to controlling where roots and branches form, to making fruit ripen. These chemicals are produced naturally by all plants, and they’re called plant hormones or phytohormones.

Plant hormones can also be produced synthetically. When they are added to growing plants, they can override the plant’s natural signals and cause it to change its growth pattern – make a branch here, or don’t flower yet. There are also various related treatments like chemicals which control the amount of hormones the plant produces itself, or compounds which are so similar to natural hormones that the plant responds to them in the same way. All of these human-applied treatments are called plant growth regulators or PGRs.

What do plant growth regulators do?

Plant growth regulators are a powerful technology in horticulture. There are many different types and they are used for lots of purposes.

In fact, there’s a decent chance you’ve used at least one of them yourself. A widespread class of plant growth regulator are auxins like indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) or 1-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA). These are commonly known as rooting hormones, because they can speed up the initiation of new roots on cuttings. Other examples are ethylene which promotes fruit ripening, and cytokinins in “keiki paste” which triggers growth from axillary buds.

But in the context of tradescantias and other Commelinaceae, when we say “plant growth regulators” (like in discussion of the ‘Nanouk’ conspiracy theory) we’re almost always referring to one specific type: gibberelin inhibitors.

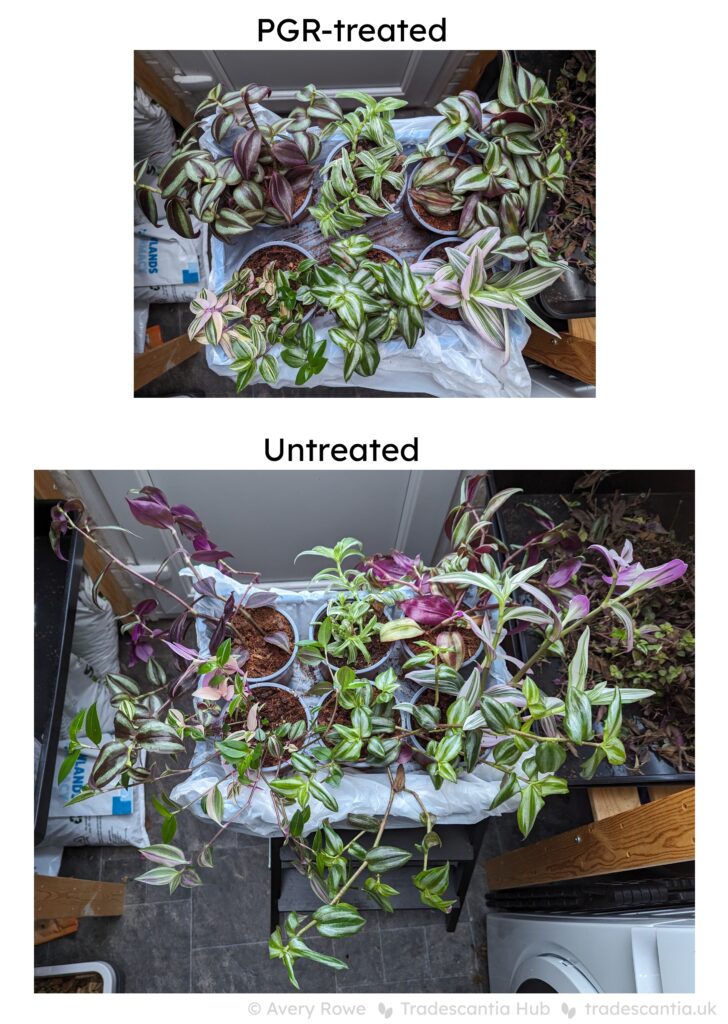

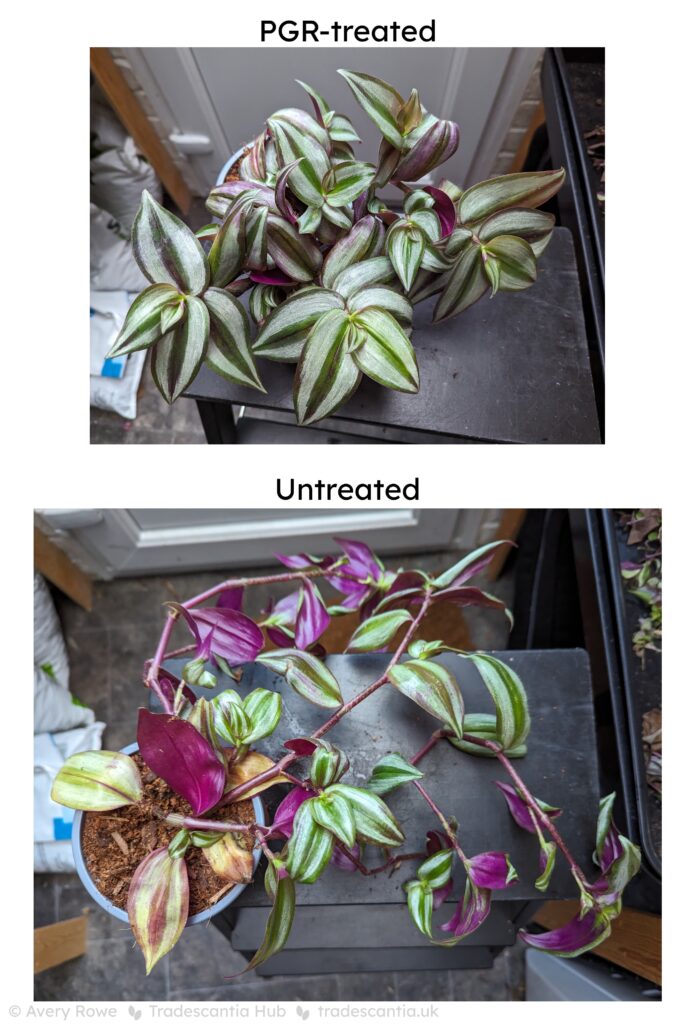

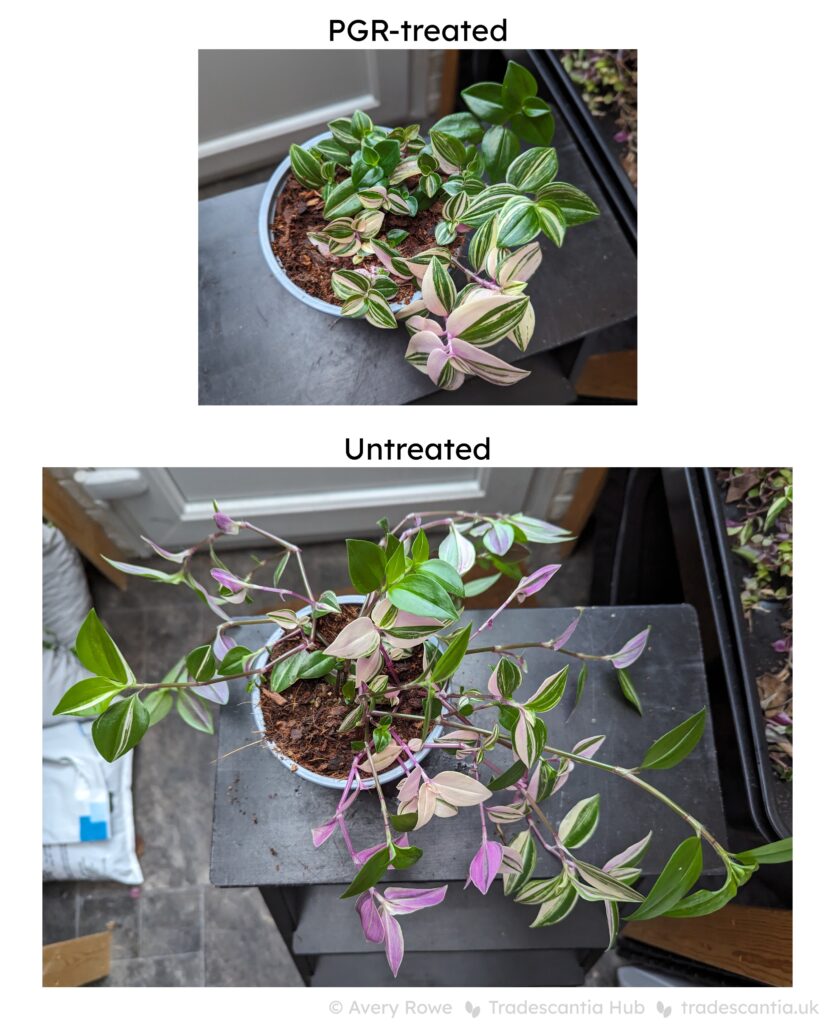

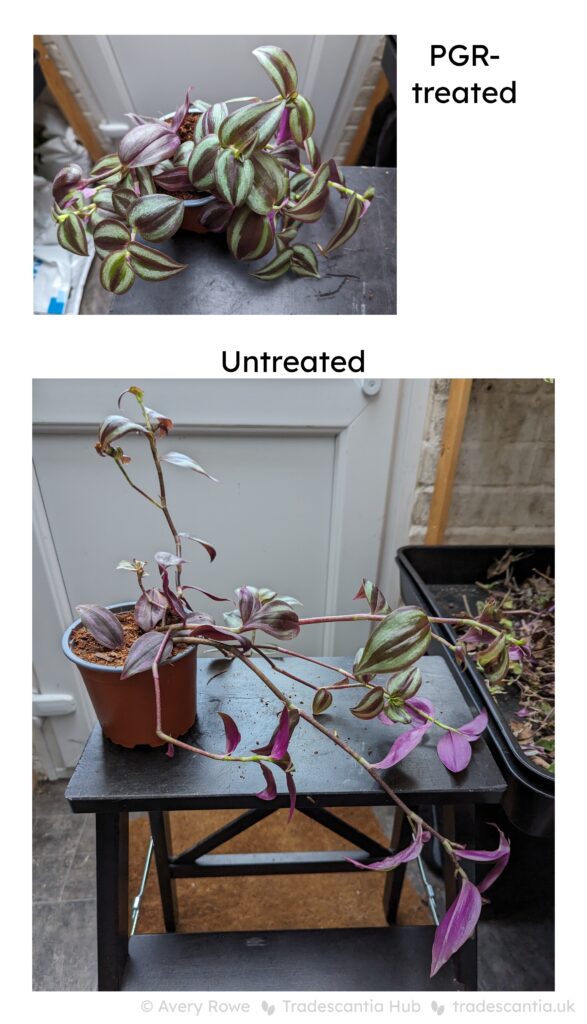

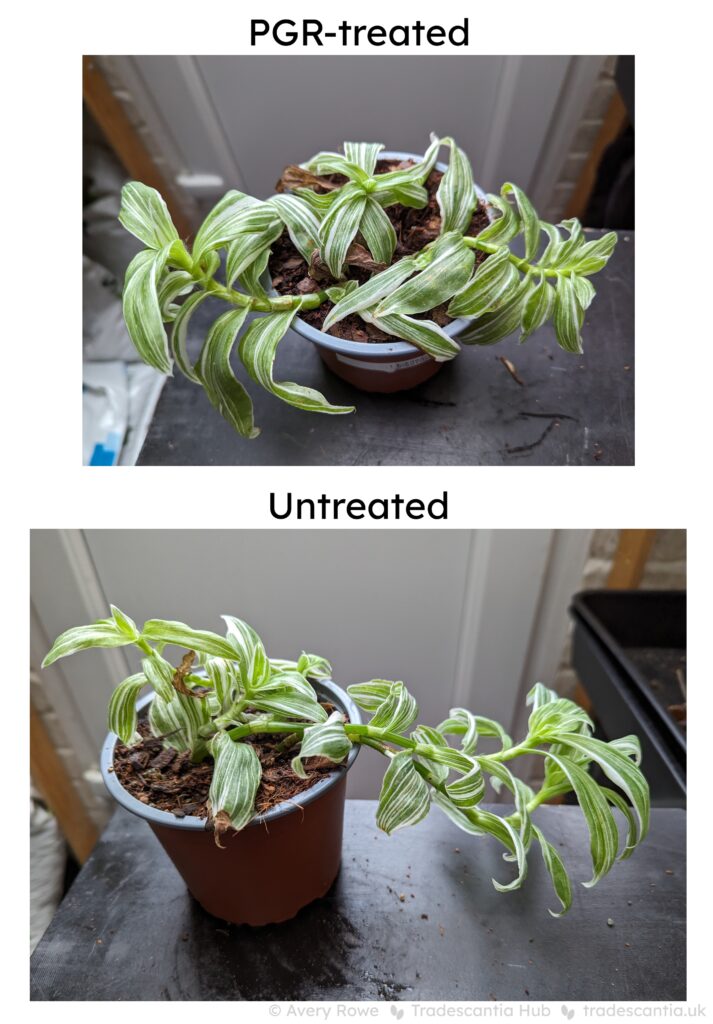

Gibberelins are an important class of plant hormones which generally contribute to the growth of stems. They make internodes (the empty stem between leaves) longer, reduce branching, and make leaves larger. Gibberelin inhibitors have the opposite effect, because they stop gibberelins from working. So the result is a plant with smaller, closely-packed leaves on compact and highly-branching stems.

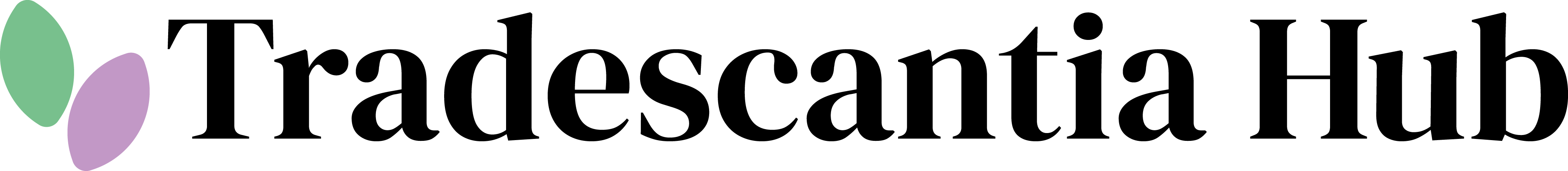

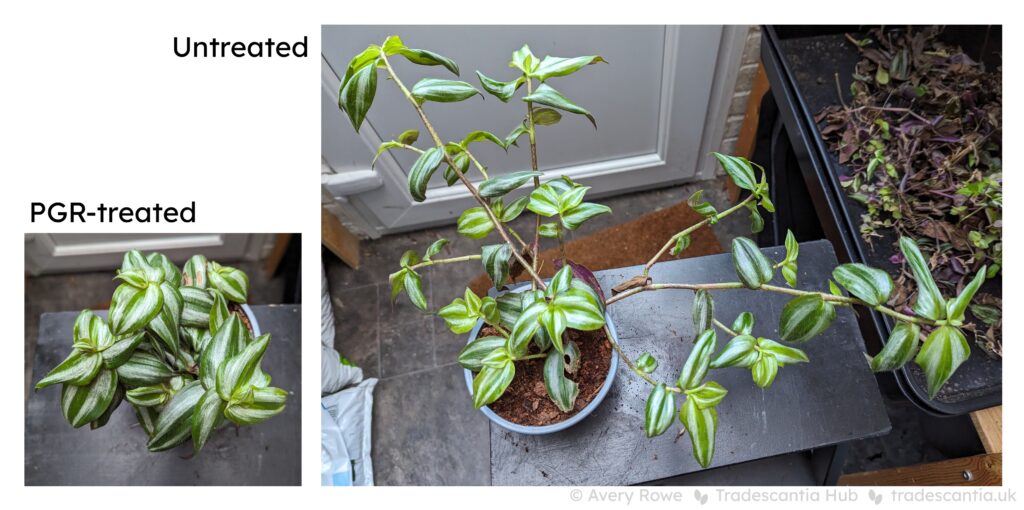

Here are two identical trays of plants when I potted them up.

I treated one tray with a gibberelin inhibitor called paclobutrazol, and left the other tray untreated. Here they are again after three months of growth in the same conditions. The rest of this article is illustrated with more photos of these plants. You can read the full details of my experimental procedure at the end of the article.

Why are plant growth regulators used?

Tropical tradescantias are notorious for their fast growth and long, sprawling stems. Those can be very desirable traits for home growers. A hanging basket will quickly start to cascade, a groundcover will soon fill an empty space, and one cutting can turn into many in no time.

But it can also be an inconvenience. If they’re not pruned and maintained, those long stems are fragile and vulnerable to being damaged or broken off. Multiple pots grown side by side will soon start rooting into each other’s soil with no sense of personal space. And a few cuttings planted in a small pot will end up leaning out in all directions leaving bare soil visible.

Gibberelin inhibitors are used by commercial growers, to keep their tradescantias under control in the challenging conditions of mass-production. A large nursery doesn’t want to waste their workers’ time on picking up and re-planting broken stems every time a tray of tradescantias is moved. And they don’t want to produce “ugly” plants that sprawl wonkily out of the pot and leave the soil exposed.

Instead what they want are large quantities of compact, uniform, and sturdy plants which will survive international transport unharmed, and which will look attractive to the average garden centre customer even after sitting on the shelf for weeks. That’s what gibberelin inhibitors achieve. Growth is slowed down, the stems are kept short, and the leaves are small and packed close together.

Are growth regulators harmful to plants?

No. Commercial growers wouldn’t be successful if they were sending out dead or dying plants. Growth regulators don’t hurt plants. What they do is cause temporary, but potentially drastic, changes to growth. Changes which can make them more confusing to identify or care for, particularly for people who are already familiar with tradescantias.

Treated and untreated plants of the same cultivar can look very different. Sometimes a PGR-treated plant of one cultivar looks more like a different cultivar than itself! For collectors who are interested in new and unique types, it can be frustrating to realise that a plant which looked so unfamiliar in the shop turned out to be a common cultivar with a temporary makeover.

When growing a PGR-treated plant, it can be harder to “read” to figure out what it needs or whether it’s healthy. Treatment initially slows growth almost to a standstill. This means that many of the signs that are usually helpful to monitor plant health are not available. With an untreated tradescantia, it’s easy to observe the shape and colour of the newest leaves in order to judge whether it’s getting the right amount of light and nutrients. But you can’t do that if the plant doesn’t grow any new leaves for weeks after bringing it home.

The slowed growth means that the plant will be using much less water and nutrients than it would in its natural state. That makes it very easy to unwittingly overwater or over-feed. And because growth is so slow, it can take a long time before the signs of a problem become apparent. Treated plants are also more reluctant to grow new roots, which means that cuttings can fail (very unexpected and disconcerting in a tradescantia!), and repotting or other root disturbance can be harder to recover from.

If a treated plant makes it through the early stages without being inadvertantly harmed, the next step is growing out of the PGRs. Depending on the exact chemical, the method of treatment, the plant itself, and other mystery factors, the effects of the treatment can last anything from a few weeks to a year. But it is always temporary, and the plant will always eventually return to its natural state. When this happens, it can be even more confusing and worrying to its owner.

If a previously compact and slow-growing plant suddenly begins stretching out long stems and larger leaves, people will often attribute it to etiolation or “legginess” from low light. But in fact it may just be the re-establishment of natural growth for a sprawling groundcover species, and no amount of light will return it to its chemically-induced former state.

Conversely, a treated plant could sit in shade for months and all the while maintain the bright pink or purple leaves that it grew in its intensely-lit nursery. When the PGRs eventually wear off and it starts making new growth that’s pale or green instead, it can be hard to understand that the light was too low all along and it’s only just started showing it.

Are plant growth regulators a scam?

No. Growers don’t label plants to specify that they’ve been subject to PGRs, so when enthusiasts learn that they’ve bought a treated plant and that it’s different from what they expected, they sometimes feel scammed or lied to. But the word “scam” suggests a malicious attempt to mislead people in order to take their money and disappoint them. In reality there’s no malice behind the use of PGRs in mass production. As I’ve written about before, it’s really more of a miscommunication.

Commercial growers mostly don’t know – or care! – that some houseplant fans are dedicated collectors who like to get a particular species or cultivar and grow it indefinitely. Mass producers know that most of the plants they sell will be bought impulsively based on visual appeal at a shop, kept for a few months or a year, and then discarded or killed through neglect.

For those customers (and most of them are probably not readers of this article), a PGR-treated plant is a great deal. They can buy a plant because they like how it looks, and it will stay that way for a good while at home even if they don’t do much to look after it. In contrast if they were to buy a small untreated pot of a tradescantia and stick it on a shady table with no care, it would only take a couple of weeks before it was so pale, sprawling, and ugly that they’d regret ever bringing it home.

Growers aren’t deliberately trying to trick you into believing a PGR-treated plant is a new cultivar. They just have no idea that you’d care whether or not it was a new cultivar.

If you feel betrayed by the use of PGRs in commercial growing, simply embrace the fact that you might not be the target market for those plants! You want something different from what mass producers are offering, and that’s okay. Think of yourself as a wine conoisseur who would be unsatisfied with the offerings at the local supermarket. It just means you will need to change the way you think about buying plants, to save yourself from future disappointment.

How do I tell if a plant has been treated with growth regulators?

If you own a plant, or can watch it for more than a few weeks, it will be pretty easy to tell it’s been treated by the slowed or suspended growth. But if you’re in a shop and wondering whether a plant on the shelf is under the influence of PGRs, that’s obviously not an option.

As I’ve been implying throughout this article, the easiest trick is to consider the source of the plant. PGRs are almost exclusively used by very large-scale growers when mass producing plants. Not only that, they are essentially always used by these growers for tradescantias. So the way to identify PGR-treated plants is to identify commercially mass-produced plants.

If you’re buying from a local nursery that grows all their own plants, or ordering cuttings from a specialist or collector – you can pretty safely assume the plants are not mass-produced and not PGR-treated.

If you’re shopping in a garden centre, hardware store, supermarket, or general houseplant shop (including online) – then they almost certainly didn’t grow the plants themselves. So they must be bringing them in from elsewhere.

Sometimes they’ll use small local nurseries. If this is the case the shop will be keen to make you aware of it with signs and labels about their producers. The nursery’s own branding will probably be on display (and might look a bit amateurish or old-fashioned). Many nurseries have a very specific niche so there might be a stand from a nursery just containing, say, cultivars of a single species. But in temperate climates like the UK and US, it’s pretty rare to come across local nurseries that grow tropicals or houseplants.

If there’s not any obvious suggestion that the plants were grown in-house or very locally, you can pretty much assume they were mass-produced. There will probably be large quantities of identical, pristine-looking plants. And most likely a wide range of different kinds of plants, with rarely more than a couple of different species or cultivars in any genus. If you visit plant shops often, you’ll probably start to notice the exact same few plants on offer everywhere. (If you zone in on the tradescantias, they’ll probably be T. mundula ‘Lisa’, T. zebrina ‘Burgundy’, T. cerinthoides ‘Nanouk’, and T. pallida ‘Purple Pixie’.)

There are a few specific producers which you might recognise from their branding. Eden Collection often add a little wooden tag that says “bambino”. Dümmen Orange use characteristic purple plastic pots. Costa Farms in the US use the label Exotic Angel Plants and often have a large tag that says “hi, my friends call me ___”. If you buy a tradescantia from any of these producers, it will almost certainly have been treated with PGRs.

Recognising PGR treatment by its visual effects is also possible. But it generally requires comparing against what the species usually looks like, which means being able to identify the species at a glance. For example, T. zebrina stems are always long and sprawling. So if you see a T. zebrina plant where the leaves are packed so close together the stem isn’t visible, you can be sure that’s not natural.

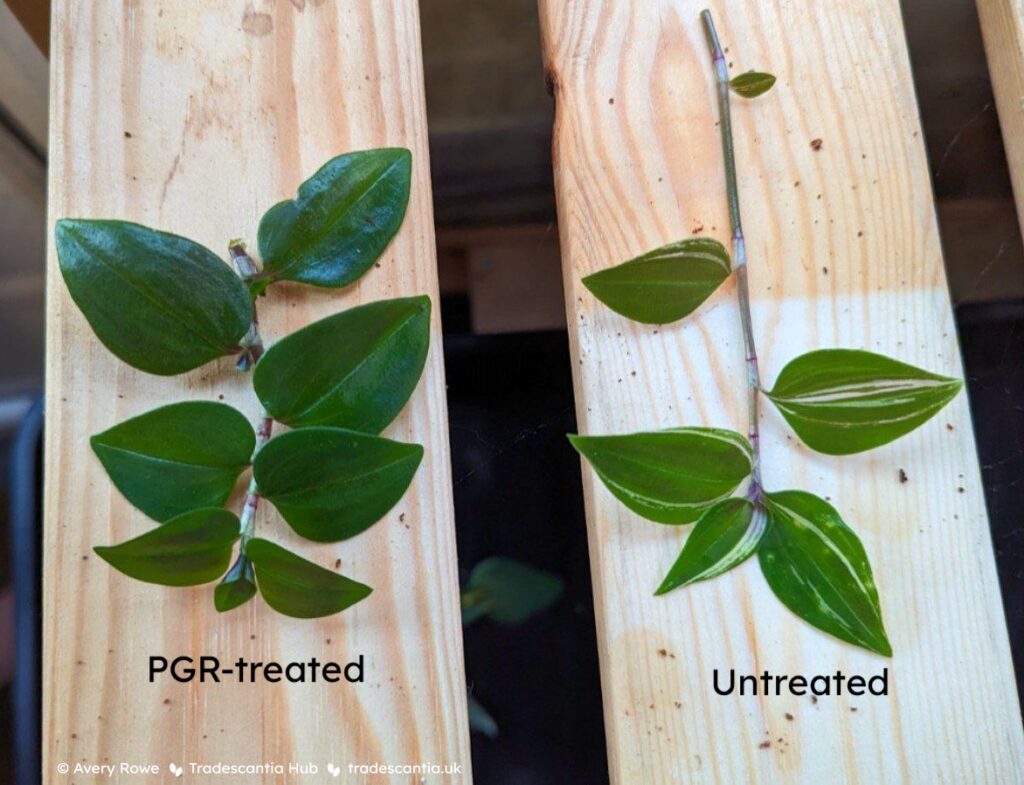

One feature that’s often quite obvious is the change in leaf size along a growing stem. When PGRs are applied, existing leaves stay the same size, but the new leaves don’t come out as big. The result is a stem where the leaves get progressively smaller towards the growing tip. In contrast, a healthy untreated plant will have leaves that start small near the base of the stem, and then get bigger towards the growing tip.

How do I get rid of plant growth regulators?

The effects of PGRs are always temporary. So even if you do nothing at all, they will wear off eventually.

But you can usually speed up that process a bit. PGRs are absorbed by the plant when they’re applied, but they can also leave residue in the soil which then keeps getting taken up by the plant over time. So the quickest way to get rid of the effect is to get rid of the soil – either by taking cuttings and discarding the root ball, or by removing as much soil from the roots as possible and repotting.

This is a bit of a risky approach, because as I mentioned above PGR-treated plants are often more reluctant to root. So taking cuttings or repotting a recently-treated plant can cause it to decline. You can give your plant the best chance of survival by keeping it in high humidity (like in a box or covered with a bag) and a warm, bright spot.

Can I use plant growth regulators at home?

Probably not.

Most countries have rules about what kinds of chemical treatments can be used in which ways. Plant growth regulators are usually restricted to professionals and can’t be sold for home use. They’re very powerful chemicals which are difficult to use correctly, and can be hazardous. And where they are available, it’s usually only in commercially-sized quantites (at corresponding commercially-sized prices).

In the UK, paclobutrazol is not permitted for home use. I was able to get professional access to use it for research. But it’s not sold at garden centres, and you shouldn’t try to buy it elsewhere unless you have a professional need and the knowledge to use it safely.

If you really love the look of PGR-treated plant, you can prolong the effect by leaving it undisturbed in the original pot and soil for as long as possible. But it will always wear off eventually – sadly you’ll just have to replace your plants regularly to maintain the look.

Details of the experiment

I tested six different Tradescantia cultivars: ‘Violet Hill’, ‘Burgundy’, ‘Minima’, ‘Lisa’, ‘Nanouk’, and ‘Albovittata’. I chose these as some of the most common commercially-produced cultivars – the plants buyers are most likely to encounter and most likely to have been treated with growth regulators.

For each cultivar, I potted up two containers each with five fresh cuttings. I used the same potting medium (a coir and bark chips mix) in the same 12cm pots with drainage holes, and did my best to take cuttings which were as similar as possible in size. I then allowed the cuttings to establish for 12 days. I randomly assigned one pot of each cultivar to be the control and one to receive the growth regulators.

To prepare the treatment, I began by dissolving 0.3g of paclobutrazol in 10ml of pure ethanol. I then diluted it with 490ml of water, for a total of 500ml. To dilute it further, I extracted 5ml of the solution and added another 495ml of water to this. The end result was 500ml of solution at a concentration of 0.006g/l (0.6%).

I applied 80ml of the final solution to the treatment containers, giving a dose of 0.48mg per plant. I chose this dose based on the established recommendations from a literature review (Henry, 1990).

I kept the control and treatment plants in separate trays to avoid any contamination from watering run-off. I placed the trays side-by-side in natural light, and swapped their positions periodically to make sure they experienced the same growing conditions. I watered both trays at the same time when the soil became dry.

I did not prune, repot, or otherwise manage the growth of either set of plants. I took photos to document the differences between them three months after applying the treatment (included in the article above) .

Found this article useful?

If you want more great resources like this, you can help me keep making them with a regular payment on Patreon.

References

Henry, R.J. (1990). A Review of Literature Concerning the Use of Growth Retardants on Tropical Foliage Plants. Commercial Foliage Research Reports, article RH-90-10. Internet Archive link.