Skip to: Species // Trade names // ‘Quadricolor’ // ‘Variegata’ // ‘Tricolor’ // ‘Laekenensis’ // ‘Lisa’ // References

This plant has had a lot of names.

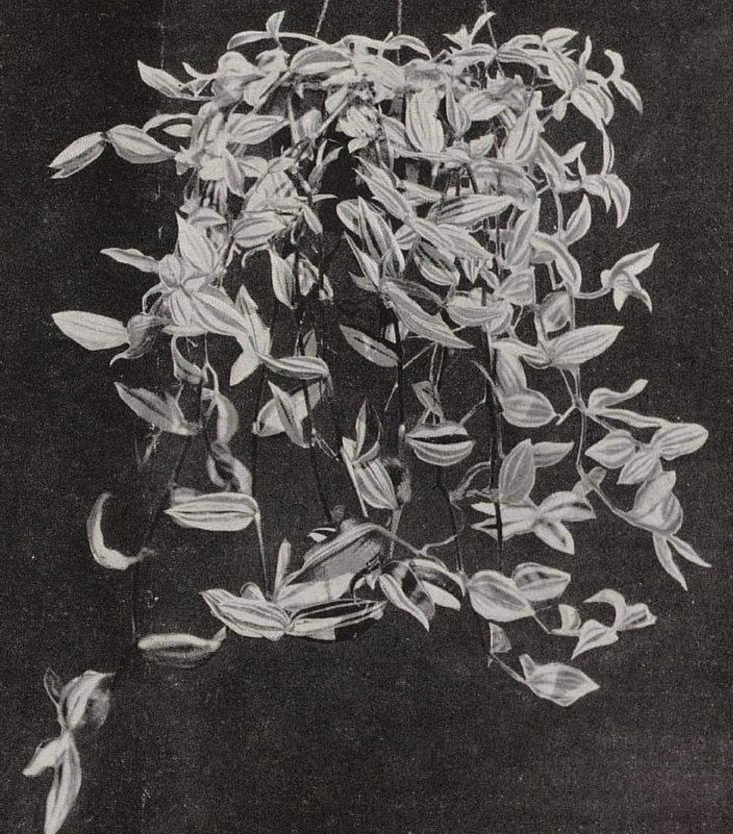

You might have seen the cultivar sold as ‘Variegata’, ‘Tricolor’, ‘Carnivale’, ‘Laekenensis’, ‘Tricolor Minima’, ‘Rainbow Hill’, ‘Pink Princess’, ‘Quadricolor’, ‘Rainbow’, ‘Venetian Colors’, or ‘Laekenensis Rainbow’. Every single one of those listings is for a clone of the exact same plant. And it turns out that none of those names is correct.

My job as ICRA is to work out which name is correct for every cultivar in the genus, and this one has taken me a long time to clear up. At one point I thought I had the answer, but it turned out I’d missed something and there was another whole vein of confusion to uncover!

I finally have a definitive answer, and it’s a surprise. The correct name for this plant is Tradescantia mundula ‘Lisa’, because the name was established in a plant breeders’ rights registration (a form of legal protection for plants).

In this article I’ll start by confirming the correct species. Then I’ll go through the invalid trade names, and the popular names ‘Quadricolor’, ‘Variegata’, ‘Tricolor’, and ‘Laekenensis’ to explain why they aren’t correct. Finally I’ll cover the definitive answer and explain where it comes from.

What species is it anyway?

When naming cultivars, the species isn’t actually required. The rules state that cultivar names have to be unique within their genus, so [genus name + cultivar name] is all that’s needed to identify them unambiguously. That’s because some cultivars are hybrids or unknown species, where it might actually be impossible to give anything more than just the genus.

Thanks to that rule, Tradescantia ‘Lisa’ is an equally correct name for this plant. But in this case, we actually can give an exact species – Tradescantia mundula.

It’s often misidentified as Tradescantia albiflora. But that’s actually not a valid species name at all, it’s now an outdated botanical synonym. It refers to the same species as Tradescantia fluminensis, which is another common misidentification given for this plant.

This whole group of species were studied in depth in a recent research paper (Pellegrini, 2018). Thanks to that research, we can easily rule out T. fluminensis (and its synonym T. albiflora) for this plant, because that species has completely hairless stems and leaves. Instead, this cultivar has rough hairs scattered along the stems and leaves, which means it perfectly matches the description of the species Tradescantia mundula.

And if that wasn’t enough to be sure, Pellegrini actually included photos of this cultivar in the study – and specifically identified it as T. mundula. So we have a definitive and very up-to-date species ID for this plant, verified by a botanist.

The plant is also sometimes mislabelled as the species Tradescantia zebrina, which is not so closely related. This mistake probably comes from confusion over the reused name ‘Quadricolor’ – more on that later.

Now we can get on with working out what the cultivar itself is called.

Ruling out some trade names

Some of the names this plant is sold with are easy to rule out. If they’re not very widely-used and they’ve never been published in hardcopy, they are just “trade names”. That means they don’t obey the rules, and they can’t be accepted as valid.

So we can quickly dismiss ‘Carnivale’, ‘Pink Princess’, ‘Rainbow’, ‘Rainbow Hill’, and ‘Venetian Colors’. They are all very recent, unpublished, and not universally used.

‘Quadricolor’? Nope!

This name has become used in recent years by commercial mass-producers. So you’re likely to see ‘Quadricolor’ on the label when you find this plant in a garden centre. It was first used in 1995 (Floricode, 2022). Although it hasn’t yet been described in hardcopy, as ICRA, I could potentially accept it as correct because it’s so commonly used.

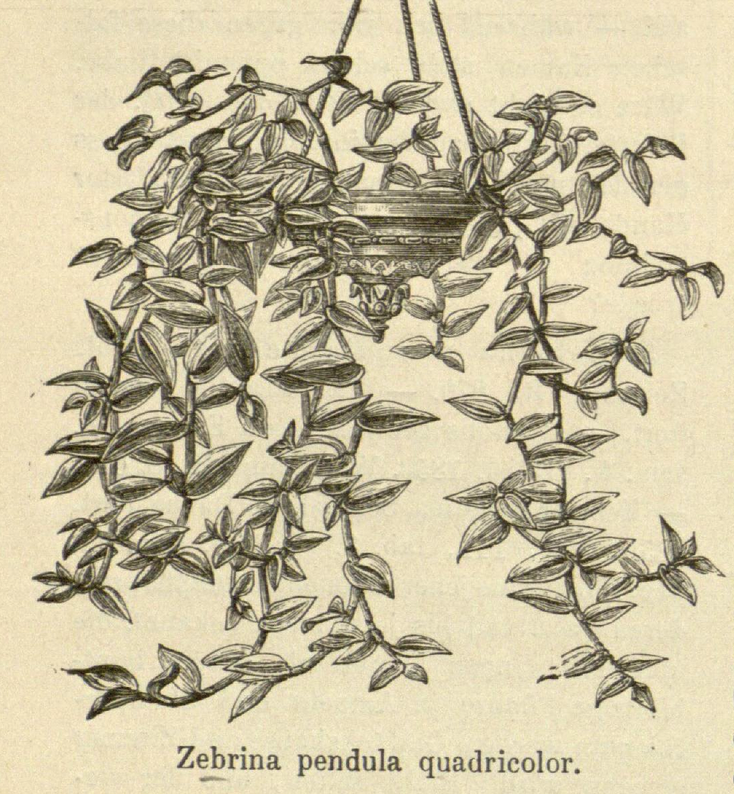

But the name is invalid, because it’s not unique within the genus. A completely different plant was given this name in 1884 – Tradescantia zebrina ‘Quadricolor’ (Regel, 1884, p. 124-125).

T. zebrina ‘Quadricolor’ is a lot less widespread – it circulates among collectors, but it’s not mass-produced or sold by many nurseries. So this name causes a lot of confusion and disappointment. People who are searching for T. zebrina ‘Quadricolor’ come across a cheap plant labelled ‘Quadricolor’ and think they’ve got lucky, but later realise that the plant they bought looks nothing like what they were searching for, because it’s a completely different species.

A new cultivar can’t be given the same name as an existing cultivar, so ‘Quadricolor’ is ruled out.

‘Variegata’ – wrong again

This name is often used by tradescantia nerds and collectors, who love to make up scientific-sounding Latin names for existing cultivars. Some people mistakenly think that all cultivar names must be in Latin – or that using Latin sounds more official or legitimate somehow. But in fact, the very opposite is true. The rules for naming plants specifically ban new cultivars from being named in Latin, and that rule has been in place for over 60 years!

Aside from the Latin problem, this name also breaks the rule of being a reused name. Another, much older cultivar was given this name in 1862 – Tradescantia fluminensis ‘Variegata’ (Rinz & Rinz, 1862, p. 67). (Because it was before 1959, that Latin cultivar name actually is allowed and valid.)

So once again, this name is not valid according to the rules, and can’t be accepted.

‘Tricolor’ and ‘Tricolor Minima’ – a promising lead

These are two names that have been in use for the plant for a long time. They do tend to cause some confusion – the two different names really suggest that there are two different versions of the plant. Perhaps one bigger and one smaller? But in fact, they are just used for the exact same clone, and that clone varies in size a lot.

This also causes confusion with the name ‘Quadricolor’. Once again, the two different words give the impression that they refer to different plants – one with three colours, and one with four. But really, there’s just one plant, with endlessly varying shades and patterns. You could say there are two colours, three colours, four colours, or many more – it just depends how many different colour descriptions you use!

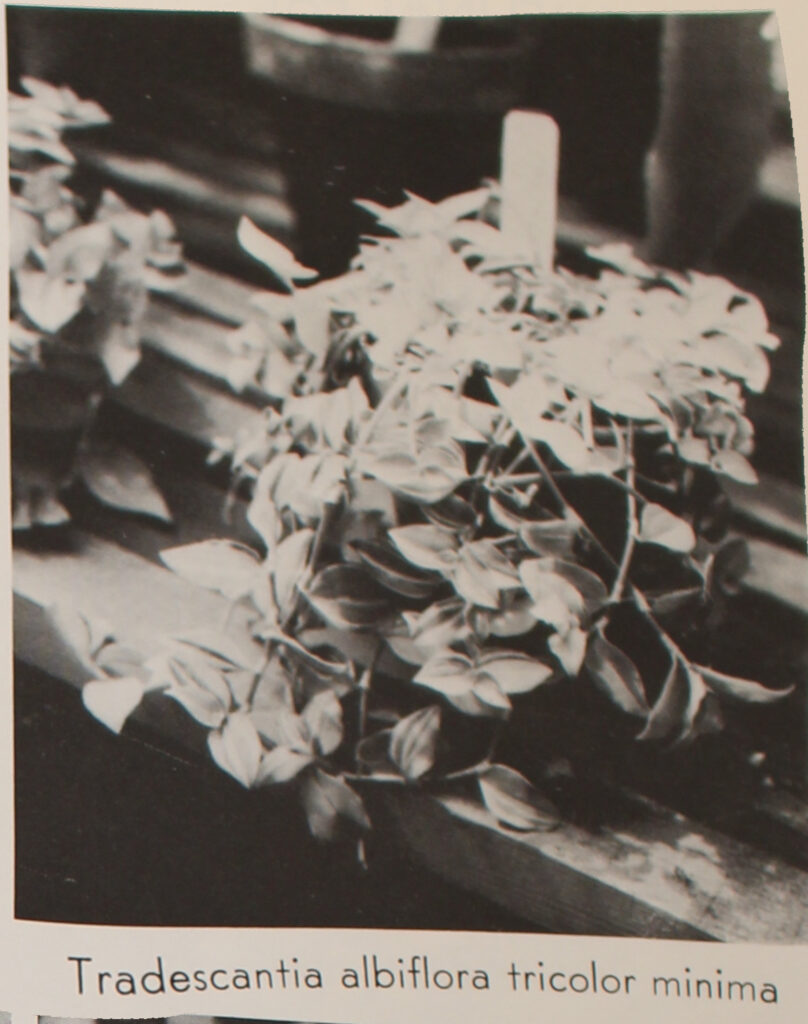

The name ‘Tricolor Minima’ is old enough to have been published in a genuine physical book (Graf, 1985, p. 785, 2462). That means it’s definitely officially established, and seems like a very promising lead for the correct valid name.

It turns out that ‘Tricolor’ was published in hardcopy even earlier (Simms, 1967). But there’s a catch. That name has once again been used before, for a different plant in 1881 – Tradescantia zebrina ‘Tricolor’ (de Candolle & de Candolle, 1881, p.318). It’s not yet clear whether that’s going to be the accepted name for a cultivar, or whether it’s actually a synonym for yet another different name. So ‘Tricolor’ may or may not still be “available” to use.

So far, it’s looking like ‘Tricolor Minima’ is the most valid name. Published in hardcopy a long time ago, still widely used, definitely unique within the genus, and follows all the other naming rules.

‘Laekenensis’ and ‘Laekenensis Rainbow’ – a wild goose chase

These names were being used in just a few places, but one of them was Glasshouse Works – a longstanding nursery in the USA. That seemed like a promising sign that the name might be pretty old, and could even have priority over others.

I did some searching, and came across a very old magazine article from 1908, about a plant called ‘Laekenensis’. It described green foliage with random amounts of white variegation tinged in pink. That sure sounds like the right plant! Another source from a few years later (Schmidt, 1914) even contained a very blurry photo.

I was pretty convinced I’d tracked down the origin for the plant, and its correct original name.

But, a bit more research revealed I was wrong. In fact, Glasshouse Works had applied the name to the wrong plant. I found a clearer photo from the time the plant was released (Möller, 1908), and books from throughout the century (Graf, 1959; Graf, 1985). They all showed that the names ‘Laekenensis’ and ‘Laekenensis Rainbow’ (used interchangeably) refer to a completely different plant – the cultivar that we now know as Tradescantia fluminensis ‘Lavender’.

That’s confirmed again by the fact that the world-leading botanical authority Kew Gardens considers the invalid species Tradescantia laekenensis to be a synonym for the species Tradescantia fluminensis (POWO, 2022) – because that’s the species the cultivar ‘Laekenensis’ actually belongs to.

‘Lisa’ – a surprise winner

This name was registered for plant breeder’s rights in the Netherlands (Bastiaansen, 1992) – the equivalent of a plant patent, it’s a way of legally protecting a newly-created plant so that no-one can propagate it without permission. The documents were obscure and hard to find, because the rights were surrendered in 1997 so the records weren’t in an active database. But when I eventually did find the original application, it was both bizarre and game-changing.

There’s a detailed botanical description of the plant. It has small, slightly asymmetrical, pointed leaves. The foliage is randomly variegated with yellow or creamy-white, tinted with pink. It often produces pure-green and pure-white stems. The description is precise down to the detail of the line of fine hairs that runs along the stem – there’s absolutely no question that it’s describing this plant.

There’s a claim that the plant is a new variety and hasn’t been sold or distributed anywhere in the Netherlands or abroad (required to apply for plant breeder’s rights – just like an invention must be new in order to be patented). This is almost certainly untrue, because there are photos that seem to show exactly the same plant in earlier books (Graf, 1985) and magazines (Simms, 1967).

There’s also, most strangely of all, a claim that the plant was created as a cross between Callisia repens ‘Bianca’ and an unnamed Tradescantia plant. There is no evidence of any hybrid occurring between Tradescantia and Callisia repens – intergeneric (between different genera) hybrids are always rare. And the plant itself has now been verified by a botanist as belonging to the species Tradescantia mundula.

So the application is definitely weird. Maybe the applicant simply found it growing among other Commelinaceae plants, and made a best guess about its parentage and origins. Maybe they really believed it was a new mutation for some reason, or maybe they just knew that no-one else had protected it before and decided to make the most of it.

In any case, the legal protection was granted. And the only rule in the entire system of cultivar naming that takes precedence over absolutely all others, is that a name given in legal protection has to be accepted as correct. Even if…

- We have suspicions about the information in the legal protection – it doesn’t matter if we think the specified parentage is wrong, because the Dutch legal authorities accepted it.

- The legal protection is no longer in place – if it’s been surrendered early, or expired after its normal 30-year limit, the previously-protected name still takes precedence.

- Other names have been established and become more widely used for the plant since – they are still overriden by the original protected name.

- The protected name itself breaks other rules about format or anything else (although luckily in this case, it’s a good name which would be valid anyway).

So all the other leads about which name might have come first, and all the other research about which were the most commonly used – all that gets overriden. ‘Lisa’ must be accepted, permanently, as the correct name for this plant.

Clearing up this cultivar has been a strange campaign, full of dead ends, misleads, and mistakes. But it turns out there was never any need to determine priority and validity to decide which of the widely-used names to accept. The right name was hiding in some old legal documents all along, and there’s no decision to make at all – it’s entirely out of our hands.

It could have been much worse – many legally protected plants are named with nonsensical codes or strange formats. At least ‘Lisa’ is a simple, pronounceable, and unique name! I’m sure this information will be unpopular for some people. Bringing back this correct name means there will be some upheaval to fix and stabilise things again, after all these years of using so many different wrong names. But eventually we’ll be able to discard all of the confusing, reused, or otherwise invalid ones, and finally give this plant its definitively right name.

References

Rinz, S. & Rinz, J. (1862). Verzeichniss der verschiedenen feinen Tafel- & Oeconomie-Obstsorten, Gehölze für Garten-Anlagen, Gewächshaus-Pflanzen [Directory of various fine table & economy fruit varieties, shrubs for garden plants, greenhouse plants]. Internet Archive link.

de Candolle, A. & de Candolle, C. (1881). Monographiæ phanerogamarum. Masson. Biodiversity Heritage Library link.

Regel, E. (1884) Katalog von Ferdinand Jühlke Nachfolger [Catalog of Ferdinand Jühlke’s successors]. Gartenflora: Allgemeine Monatsschrift [Garden flora: General monthly journal], pp. 125-126. Biodiversity Heritage Library link.

Möller, L. (1908). Deutsche Gärtner-Zeitung [German gardener newspaper]. Internet Archive link.

Schmidt, J. C. (1914). [Catalogue]. Internet Archive link.

Graf, A. B. (1959). Exotica 2: Pictorial Cyclopedia of Indoor Plants. Roehrs Company.

Simms, W. F. (1967). A Re-appraisal of the “Tradescantias”. Gardener’s Chronicle, 162(25), 8-9.ca

Graf, A. B. (1985). Exotica 4: Pictorial Cyclopedia of Exotic Plants from Tropical and Near-tropic Regions. Roehrs Company.

Bastiaansen. (1992, October 1). Tradescantia ‘Lisa’ [Netherlands plant breeder’s rights registration 12254]. Community Plant Variety Office. Registration document link.

Pellegrini, M. O. O. (2018). Wandering throughout South America: Taxonomic revision of Tradescantia subg. Austrotradescantia (D.R.Hunt) M.Pell. (Commelinaceae). PhytoKeys 104: 1-97. doi:10.3897/phytokeys.104.28484. Open access link.

Floricode. (2022). E-Barcodes. Internet Archive link.

POWO. (2022). Tradescantia laekenensis. Plants of the World Online. Link.

11 replies on “T. mundula ‘Lisa’: the most mislabelled tradescantia of all time?”

Wow! An incredible piece of detective work!

Super impressive Avery. Well done!

So impressed with all the evidence supplied, I’ve run off to find a magnifying glass to see if mine has the hairs on the stems and it will be getting a brand new label. Thanks Avery

‘Laekenensis’ is grown in the US. We have no record of ‘Lisa’. Sounds like that is a selected clone or an illegal rename. Kew is going to lump every cultivar with the species. They always have but that does not make it horticulturally accurate. ‘Laekenensis’ is validly published, very clear, and has priority in the tertiary/infraspecific position not the secondary/specific position. Sorry, but really have to disagree with tossing out an established name for some PBR in 1992.

It doesn’t really matter whether you agree (it’s not the name I would have chosen either) – I’m applying the rules that have been in place for decades by international agreement. If I decided to override the code whenever I felt like it, I wouldn’t be doing a very good job as ICRA!

That said, I think you’ve misunderstood. ‘Laekenensis’ is indeed a valid name, for a totally different cultivar of a different species (T. fluminensis), which originated around 1908. The cultivar this article is about is several decades more recent, and belongs to another species (T. mundula). The name ‘Laekenensis’ became incorrectly misapplied to this plant because of identity confusion, but it’s nothing more than a mistake. That’s why ‘Laekenensis’ isn’t the valid name for this cultivar – because it isn’t a name for this cultivar at all.

Thanks. I understand now. Alamy.com and agefotostock.com show ‘Lisa’ as a yellow-striped (not one bit of pink), mundula-sized variegate something like a smaller-bladed T. fluminensis ‘Aurea’ (‘Variegata’ pro parte). Those plants must not have gotten enough sun to “pink up”. Since ‘Lisa’ probably never made it to N. America, I guess it’s purely a European situation. I am concerned that if Bastiaansen falsely claimed it to be their unique, exclusive invention (ie. same clone already known as in Graf 1985), they committed fraud, rendering their production and name invalid. But if you feel it’s a distinct enough invention, I’ll take your word for it.

I’m pretty sure those ‘Lisa’ stock photos are misidentified too – they do appear to be a T. fluminensis cultivar. One of them was also tagged as “Tradescantia andersoniana”, so I’m not inclined to put much faith in the identification of the photographer!

I agree, if the ‘Lisa’ plant already existed (definitely seems to be the case), then the legal protection should not have been granted. I can’t say whether Bastiaansen were being deliberately fraudulent, or simply didn’t realise the plant had already been distributed, but either way it should have been stopped up at the time. But the fact is, it wasn’t stopped, and the Dutch plant registration board did accept the application and provide the legal protection. It would be inappropriate for me now to override a legal decision made by a statutory authority, even if I have evidence that probably should have prevented that decision from being made at the time. It’s a weird situation, but the influence of intellectual property laws on plants and naming is always pretty weird.

I think that the confusion will continue, due to the fact that the cultivar name ‘Lisa’ will not be as marketable as ‘Rainbow’ or ‘Tri-color’, and the fact that garden centers are, unfortunately, more interested in sales, than they are in identifying a plant by it’s correct botanical nomenclature.

Is reverted ‘Lisa’ (plant that has lost variegation) the same as ‘Green Hill’ or would a different name be more accurate? Or is ‘Lisa’ one that will return to the variegated form once in proper light/temp/humidity? Thanks so much for all the research you’ve done regarding all the lovely tradescantia beauties!

Yes, ‘Green Hill’ is the reverted form of ‘Lisa’. It will very occasionally regain a pink stripe, but generally the reversion is permanent.

Good to know, thank you!