Skip to: Spotting the signs // Treating an infestation

Thrips are tiny insects from the order Thysanoptera. There are thousands of different species, but they almost all feed on plants by puncturing the leaves and sucking out the liquid inside.

Outdoors and in the wild, their population is naturally controlled by predators and other factors, and they usually don’t have much negative impact on host plants. But when they attack indoor plants in artificial conditions, their population can get high enough to cause real harm to the plants.

Thrips seem to be one of the most common pests for Commelinaceae houseplants. They can be very difficult to spot, and can do a lot of damage before they’re noticed. This article is in two parts – first, a guide to recognising the signs of thrips damage, and then some tips on how to deal with an infestation.

Spotting the signs

The earliest signs of thrips can be very inconspicuous, but they can be spotted early if you know what to look for. This section will cover the common signs on tradescantia plants, roughly in esalating order. They don’t always show up in exactly the same order – they can cross over or skip stages – but this list starts with the hardest early signs to spot and ends with the unmissably obvious.

Leaf rolling

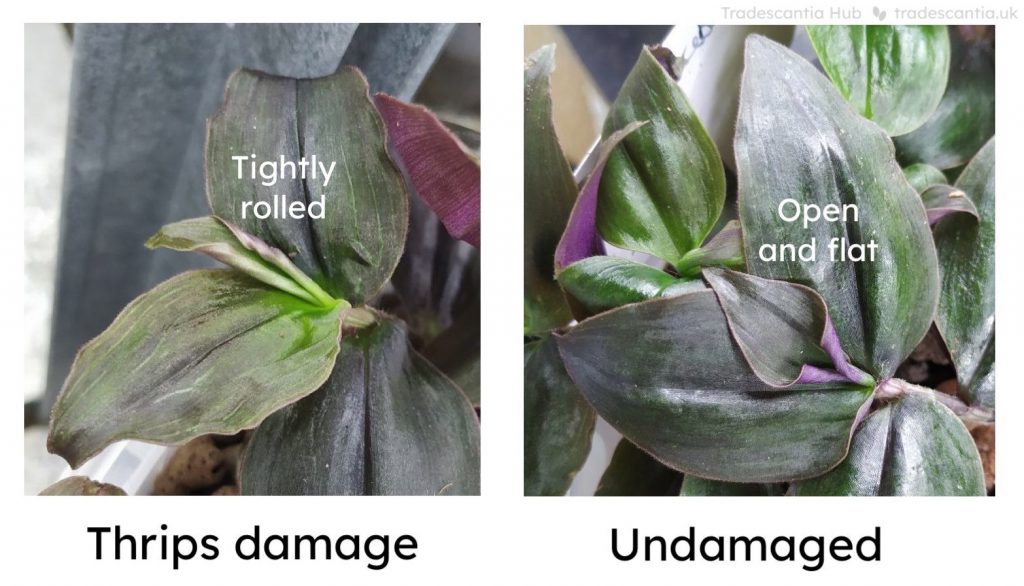

Thrips always prefer to feed on the freshest new growth, so the newly-developing leaves generally show the first signs. The very first effect is that new leaves have their edges rolled inwards. This can be very difficult to recognise, because all tradescantia leaves first emerge with their edges rolled inwards!

But when they’re being damaged by thrips, the new leaves will be rolled more tightly, and stay rolled up for longer than usual. The only way to recognise this sign is to be very familiar with the normal growth patterns of your plants, so that you’ll notice the smallest change.

Here is a comparison between two stems of Tradescantia zebrina ‘Purpusii’ – the stem on the left is damaged by thrips, the one on the right is healthy. Look at the newest leaf at the growing tip. On the damaged stem, that leaf is still tightly rolled inwards. Whereas on the healthy stem, it’s already open and flat in the middle, with just the lower corners still rolled.

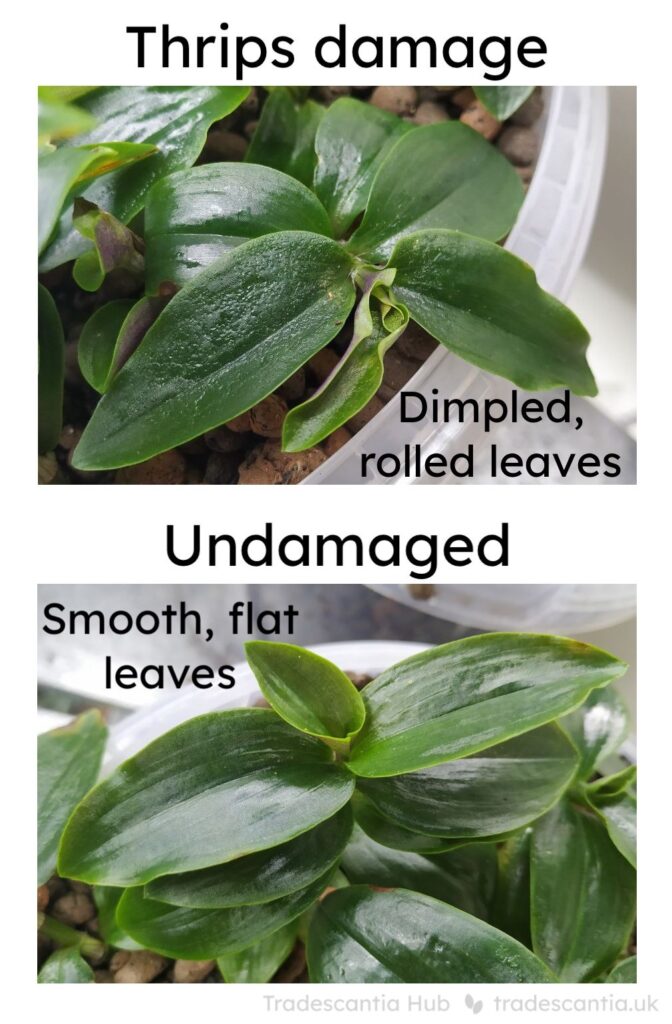

Leaf dimpling

The first visible damage to the actual leaf tissue shows up as pinprick-like dimples or pockmarks on the upper surface. This is usually most apparent on the two or three leaves nearest the growing tip, and especially near the base of the leaves where they meet the stem. In small amounts it might just look like a few little pinpricks, but over larger areas it makes the whole leaf surface look rough and bumpy.

Here is a very minor example, a Tradescantia zebrina ‘Little Hill’ leaf with just a small patch of dimples near the middle:

Here’s a more extreme case, with a comparison to a healthy stem of the same plant (a reverted Continental Group cultivar). On the damaged stem, the whole leaf surfaces have become rough and bumpy. You can also see that the newest leaves are rolled inwards more tightly than they should be.

Silver patches

This next sign is quite noticeable – as long as you’re looking at the underside of the leaves. As the damage gets worse, it becomes visible as silver speckles and patches on the undersides. Sometimes these areas are also dotted with tiny black specks (the waste from the thrips).

Here’s a leaf from Tradescantia ‘DRATRA01’ (also known as Roxxo). On the underside there are obvious silver streaks. But the same leaf from above is the usual uniform purple, and looks completely normal.

Visible bugs

For most other pests, the visible bugs are likely to be the first thing you notice. Aphids are long-legged insects which crawl over the surfaces of the stem and leaves. Mealybugs and their eggs show up as high-contrast white blobs scattered over the plant. Even spidermites, although they themselves are very small, will make obvious nets of webbing among the foliage.

Thrips are tiny – at most usually 1-2mm long, and their bodies are very narrow and flat. They also spend most of their time either hiding inside the folds and sheaths of developing leaves, or actually inside the leaf tissue between layers. So the population (and the damage to the plant) can get very bad before you ever catch a glimpse of a living, moving insect.

The nymphs (youngsters) will develop first. They are cream coloured and very small – less than 1mm long – but have the characteristic long narrow shape. If you suspect thrips, your best chance of seeing the bugs in an early infestation is by gently unrolling the newest developing leaf on a suspicious-looking stem. If you see tiny linear yellow specks moving slowly over the leaf surface, those are thrips nymphs.

Adults may not appear until much later, but when they do they are more visible. They can be up to 1-2mm long, and they’re usually black or dark brown. You might recognise them as “thunder flies”, familiar visitors if you sit in grass during summer. On tradescantias, you’ll probably see the adults crawling around on the underside or sometimes the top surface of leaves.

Brown spots

We’re now getting to the signs that are hard to miss. This one is a natural development of the silver patches from earlier. Eventually the damage goes through all layers of the leaf, and it becomes visible as brown dead spots from the top surface. For species with thinner and more delicate leaves like T. fluminensis, the damage may be visible from above immediately. With thicker and tougher leaves like T. zebrina or the T. ‘DRATRA01’ (Roxxo) from earlier, it can take a long time before the damage shows through.

Here’s a leaf of T. zebrina ‘Little Hill’ with a damaged silvery patch on the underside, showing through as a dead brown spot on the top.

Dying leaves and stems

The endgame. As the damaged spots grow and spread, eventually entire leaves will die and drop off. Because thrips are most attracted to fresh new growth, they damage the growing tips first. When the damage gets bad enough that the tip dies, the stem will make new branches lower down. The thrips will immediately concentrate on those new branches, and if the population is high then the new growth will be killed before it has a chance. Eventually the plant doesn’t have enough energy to make new growth, and the stem will die.

Treating an infestation

It’s probably impossible to prevent thrips or any other leaf-eating insects from ever reaching your plants. It’s always sensible to inspect new arrivals for problems, and consider quarantining them away from your existing plants for a week or two in case anything appears in that time. But thrips and other herbivores will always exist in the outside world, and there will always be a chance that they find their way in to houseplants – on clothes, on shoes, on pets, through open doors and windows.

Regular monitoring will help you notice the earliest stages of pests if they do appear. Once you recognise the problem, there are many different ways to handle it: some more extreme than others. These suggestions are presented roughly in escalating order, from least to most drastic. You should always start with the least drastic option possible! That will minimise the risk to yourself, to your plants, and to the environment.

Some of these suggestions are about pesticides, which can be harmful to wildlife, pets, and people. Always do your own research, check the laws and rules of your location, and follow the instructions on the label of anything you use. This information is just intended as a summary of the types of thing that might be available.

I’m also not making any specific recommendations of particular brands or products. I don’t know enough to give examples for every single type of pesticide, and what’s available varies widely in different parts of the world.

Let nature take care of it

If your plant is outside – you almost certainly don’t need to do anything. Outdoor plants are part of the ecosystem, and they will naturally support small populations of herbivores like thrips, aphids, and caterpillars. Other wildlife, as well as environmental conditions, will naturally regulate those populations so they will rarely become high enough to cause a problem for the plant.

If your plant is inside, then moving it outside – even just for a few weeks – can be an easy way to fight an infestation. Most tradescantias can survive any temperatures above freezing, so they can easily spend summer outside in temperate climates like the UK. Just try not to put them straight into direct sun, because their leaves may burn if they haven’t acclimatised to it slowly.

Let nature take care of it (with some help)

If your plants are indoors, you can help create an artificial ecosystem around them with predators which will reduce the thrips population.

Predatory mites like Amblyseius swirskii (more effective at above 20ºC) and Amblyseius cucumeris (more effective at below 20ºC) are a popular choice. They are tiny mites – even smaller than thrips themselves – which will crawl over the plant and hunt the nymphs. You can buy sachets which you hang on the plant to let the mites crawl out over several weeks, or containers of mites in loose sawdust which you sprinkle directly over the plants.

Orius laevigatus are larger insects which will also attack fully-grown adult thrips and can be distributed in loose material in the same way.

Mechanical methods

If there are a lot of flying adults, you can use blue sticky traps (not the usual yellow ones) to catch them and monitor their population. Thrips are attracted to the colour and will get stuck to the glue when they touch it, and soon die.

If the damage is visible on particular stems, it’s quite effective to just prune off the top 5-10cm that has damaged leaves. The thrips larvae will be concentrated on the new growth, so removing it is an easy way to remove a lot of the bugs. The plant will quickly make new branches and come back even more bushy than before.

Physical pesticides

The first line of attack once resorting to pesticides are those with a physical mode of action. That means that instead of containing chemical poisons, they contain substances which physically damage the insect when touched.

The two main options are plant oils and fatty acids (often called insecticidal soap). Both of these substances will kill insects which they come into direct physical contact with, but don’t have any longlasting effect. Insects that aren’t caught in the spray won’t be harmed at all, which means that hidden pests can easily escape. Because they don’t have any lasting effect, it might take multiple frequent applications to get an infestation under control. But they’re an ideal option for when you first notice the earliest signs and the pests are concentrated in just one plant or a small area.

These treatments might be labelled as things like “plant invigorator” (sometimes with nutrients added) or “plant wash”, but the important thing is always to check the active ingredients. Plant oils will contain substances like sunflower or rapeseed oil, and fatty acids will be listed as “fatty acids” or possibly “potassium salts of fatty acids”.

Physical pesticides can kill wild or friendly insects which they hit. So you should be careful not to spray them on pollinators like bees or butterflies. They are generally harmless to mammals (people and pets), although it’s best to avoid direct skin contact.

Contact pesticides

The next step up from physical pesticides are chemicals which kill on contact, and will last for a short while on the surface of the leaves. This means that bugs which miss the initial spray might still be killed later if they come into contact with the residue of chemicals on the leaves.

The most common pesticides which fit this category are a group called pyrethroids. Some common examples are lambda-cyhalothrin, deltamethrin, and cypermethrin.

These chemicals will kill wild or friendly insects which come into contact with them. Make sure you don’t spray where there are pollinators – if possible, avoid using them on outdoor plants. They’re fairly safe for most mammals, although very dangerous to cats, and it’s always best to avoid direct skin contact.

Systemic pesticides

The big guns – these are chemicals which are absorbed by the plant and distributed throughout it. That means they have a lasting effect that will kill any insect feeding on the plant, even if it never goes anywhere the chemical was originally sprayed.

A common group of pesticides which fit this category are neonicotinoids like acetamiprid. Another similar chemical is flupyradifurone.

These chemicals are very dangerous to wild insects, and to other wildlife like birds and aquatic animals – do not use them on outdoor plants. In many countries, neonicotinoids are restricted or banned because they are so harmful to wildlife. They are also somewhat toxic to people, so make sure to wear gloves and avoid any direct contact.

Conclusions

Thrips are a very common problem for Commelinaceae houseplants. They can be tricky to spot until an infestation is so bad the plant is suffering. But there are some subtle things to look out for that will help you spot the early signs of a thrips attack so you can take action.

It’s impossible to prevent pests from ever reaching your plants. Outside in nature, small populations of herbivores are normal and harmless to most plants. Indoors, you can use physical methods to reduce the population at the first sign of a problem. If that doesn’t do the trick, there are also more powerful chemical pesticides – but you should make sure to use them safely and no more than absolutely necessary.

Found this article useful?

If you want more great resources like this, you can help me keep making them with a regular payment on Patreon.

6 replies on “How to spot and treat a thrips infestation”

Excellent article, thank you! The photos of examples were really helpful.

I wholeheartedly endorse Laura’s comments and thank you

The most comprehensive article I’ve read. Thank you

It would be great if you could mention if neem oil or undiluted alcohol wipes help? I have been using alcohol but I have no idea whether I need to wash if off straight afterwards so it doesn’t burn the leaves or something.

I have signs of thrips where wholes STS are dying but can’t see any ‘bugger’. Pun intended.

Neem oil is a type of plant oil, which is mentioned in the physical pesticides section.

Isopropyl alcohol will kill insects on contact in just the same way as soap and plant oils. But it can also harm plants in high concentrations, so there’s not much reason to prefer isopropyl over another physical pesticide which would be equally effective and less risky for the plant.

If you can’t see any bugs at all, then physical pesticides (like neem oil or isopropyl) are unlikely to be effective. They only kill the bugs that they physically touch, so if you can’t see the bugs in order to touch them then you won’t be killing them either.

I loved your article. I actually work doing research in pest biological control, and your suggestions on how to fight the pest are spot on. I think it’s a super complete article. It’s great to find good, valuable information nowadays!