Correctly identifying an unknown plant is a difficult task. To do it reliably, you need to know four things:

- What all of the possible species or cultivars are to choose from.

- Which features are diagnostically relevant (and which aren’t).

- How the relevant features present in every possible species or cultivar to distinguish them.

- How to find and recognise those relevant features in an unknown or unfamiliar specimen.

That’s a lot of information, and it’s difficult to learn! Experts can spend their whole lives developing these skills in just one small group of plants.

Because of that, people often hope for easier ways to identify their plants. But unfortunately, there are no shortcuts to this process. Generally, the alternatives that people turn to are unreliable and lead to misidentifications and misplaced confidence.

ID charts don’t work

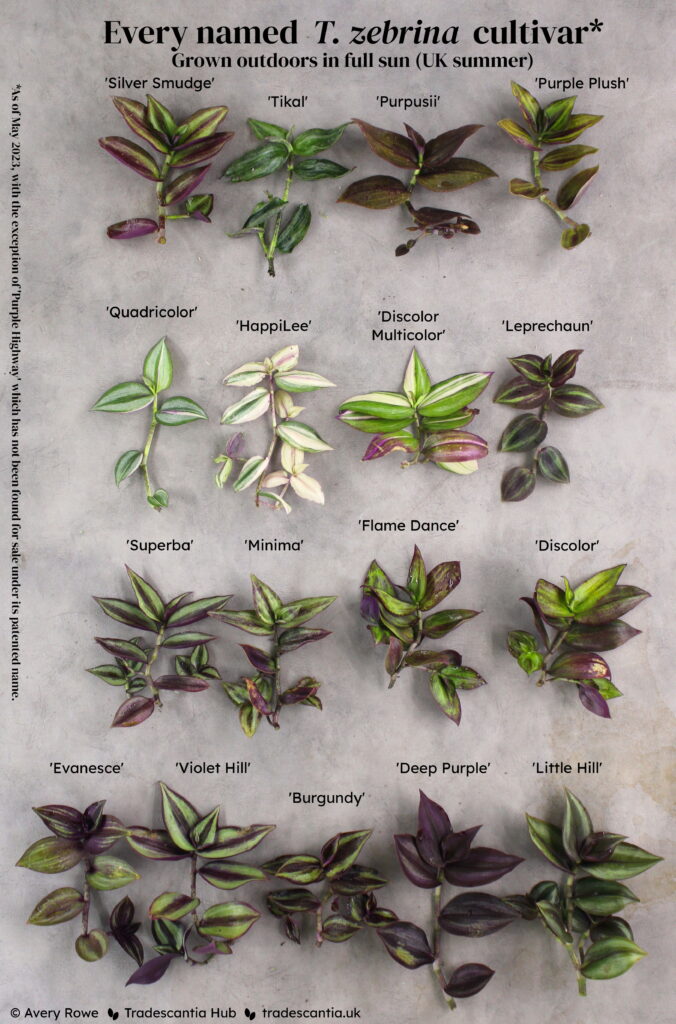

Among houseplant enthusiasts online, it’s common to share “ID charts”. They’re usually pretty pictures which show an array of attractive plants or cuttings laid out together. Which is great – pretty pictures are one of the best things about the internet.

These ID charts usually have each plant labelled on the image or in a numbered key. The neatly labeled specimens tempt people to treat them as an identification guide: just compare your unknown plant to the picture, choose the one that looks most like it, and you have your label. Sadly it’s not that easy, and using these charts is very likely to result in incorrect identification.

The first problem is that the charts are often incomplete. For a small enough target group of plants it might be possible to show every possibility in one photo – assuming whoever makes the chart actually knows about and has acccess to them all. But for bigger groups there’s no way a single image could ever show the complete set with an identifiable level of detail. If your plant isn’t one of the ones included in the photo, you’ll never get the right ID, and you might never know it if the chart is presented as if it’s complete.

The second problem is that naming errors are so common. An authoritative-looking image with incorrect labels can spread a lot of confusion when it goes viral! Even if a chart is made with entirely accurate labels, it can still only be totally correct at the time it’s published. Information gets out of date quickly – names change, and new species and cultivars arise. The older a resource is, the less likely it is to still be useful. And these charts are almost never dated, so it’s usually impossible to have any idea how outdated they really are.

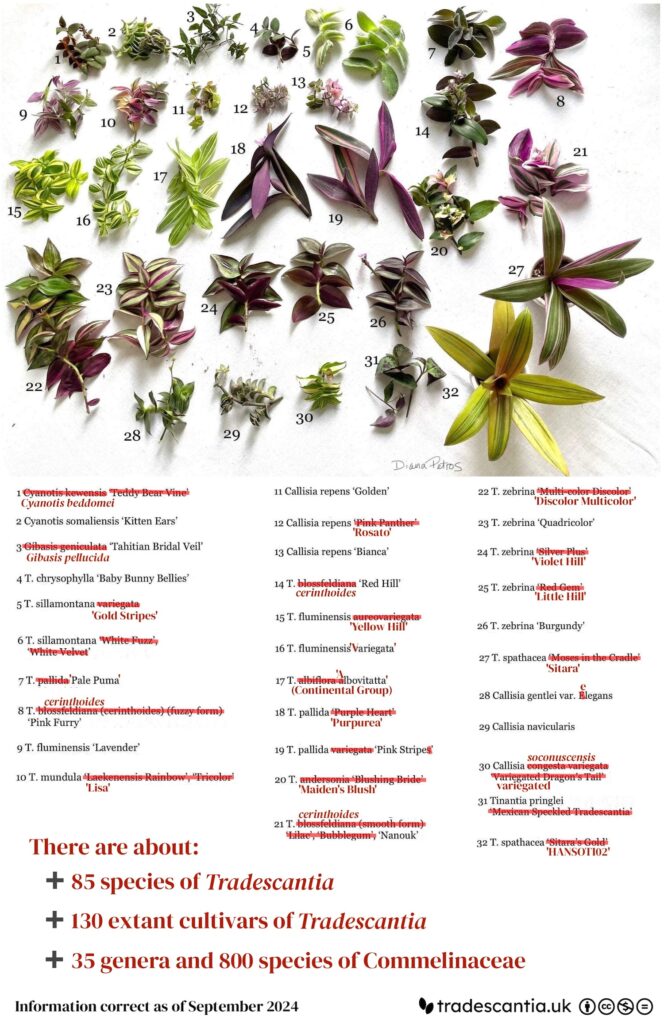

Here’s one of the most popular tradescantia ID charts out there. It was first posted in 2020 by an online shop, as a listing of the different varieties they had for sale. Since then it went viral, and now it continues to circulate several years since the original post disappeared.

In red are my notes and corrections, highlighting the incorrect names and pointing out how many types are missing from the image. The shop which first posted it had good intentions – they thought their labels were right at the time, and they didn’t make any claim that it showed every single Commelinaceae plant there is. But now it gets shared without context, and assumed to be both 100% accurate and 100% complete, which leads to a lot of misidentifications.

But even if a picture has totally accurate labels, shows a complete and defined set of plants, and is bang up to date with its information – it’s still not a good ID chart. Because there are no good ID charts. It’s simply not possible to accurately identify an unknown plant by comparing it to one photo and choosing the closest match. All plants can change their appearance in different growing conditions and different stages of life. The tradescantia family in particular are notoriously variable, but it goes for any group of plants. No single photo can possibly represent all the variations of a single species or cultivar.

In most cases, the important features that are useful for identification are difficult or impossible to capture in photos. Are there microscopic hairs along the margin of the leaf? How quickly does it grow? Does it feel velvety or bristly to the touch? How many millimetres thick is the stem? What colour are the tiny filaments inside the flower (and by the way, each flower will open for about four hours at a time, once every year or two if you’re lucky)?

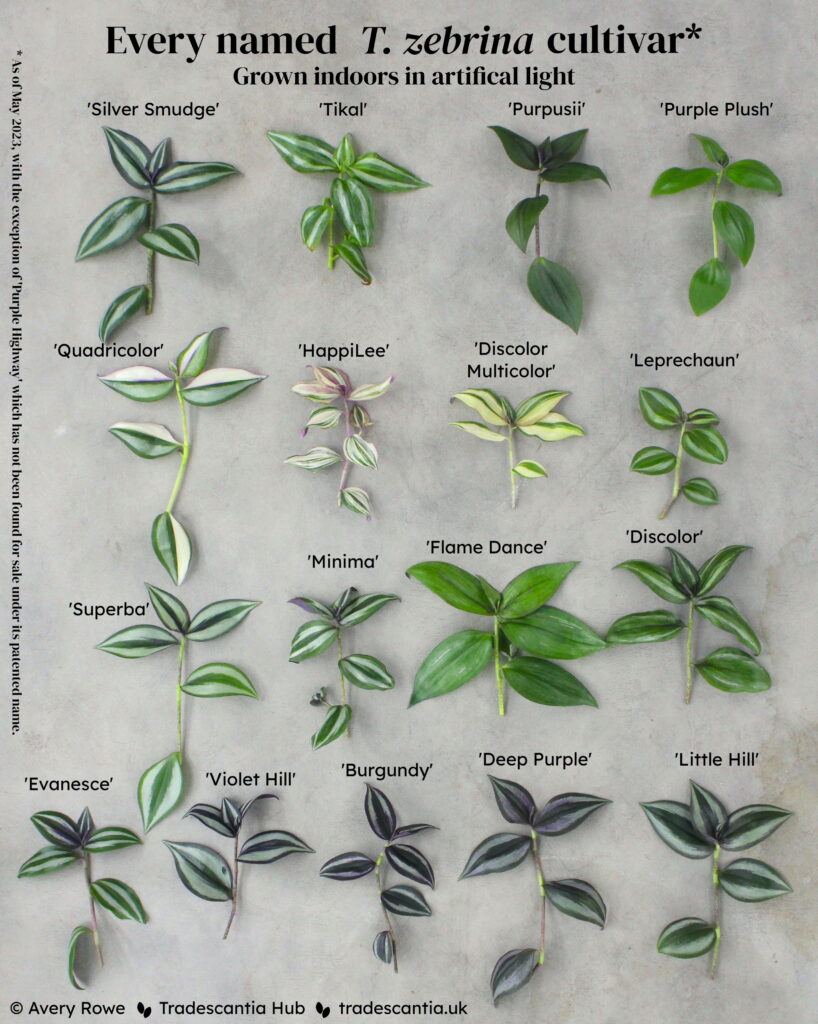

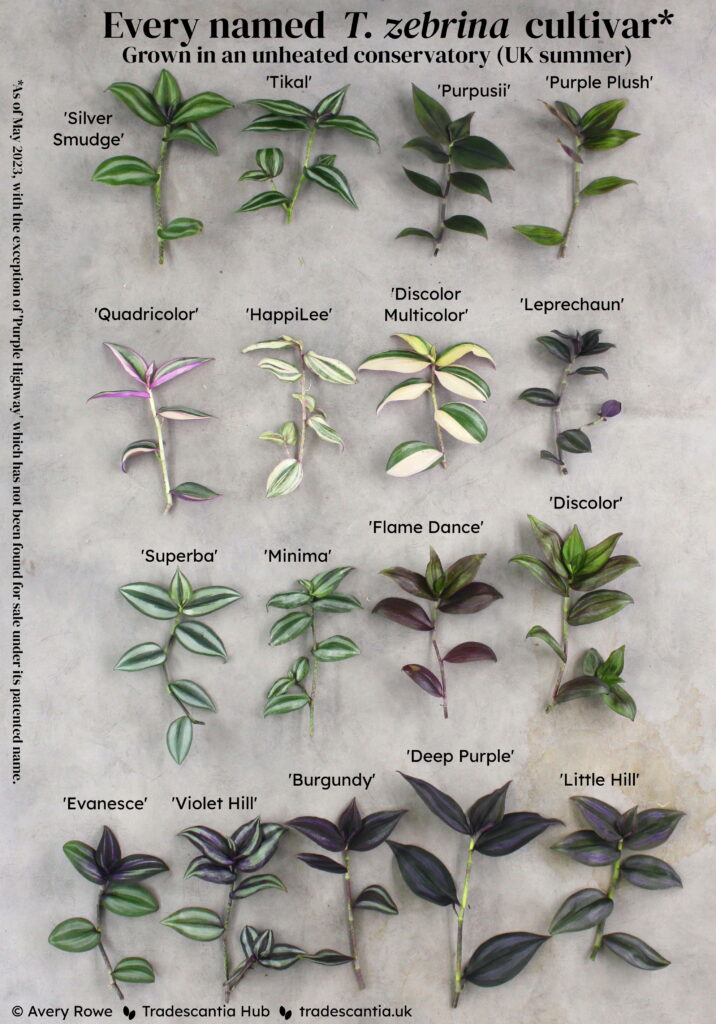

But when looking at these kinds of pictures, people pay attention to the broad features like colour and size to compare to their own plants. And those broad traits are the most variable ones! You only need to look at my arrays of T. zebrina cultivars to see how different the same plants can look in different conditions. If you tried to use each of these three pictures to identify your unknown cultivar based on shape and colour, you’d get three different answers. (I know that because people do use these images as ID charts – even though I tried to discourage it when I published them!)

ID apps don’t work

AI-based plant identification apps are another popular approach. These apps usually let you take or upload a photo of your plant, and then give you a name for it. Some of them also provide care advice and suggestions about what might be wrong with the plant. The authoritative way they give information makes people believe they are totally accurate and reliable, but unfortunately that’s not the case at all.

Machine learning models (“AI”) are good at pattern recognition. In theory, they can categorise and identify things according to the framework they’re trained in. If you give a good1 photo of a common2 plant to a good3 AI app, there’s a decent chance it will correctly identify it. But that’s not as simple as it sounds.

- A good photo means well-lit, sharp, and – most importantly – showing all the significant identifying features of the plant in question.

- A common plant means one that is well-represented in the AI’s training data.

- A good AI app means one that is well-trained based on a large amount of reliable input data, and that uses an accurate taxonomic framework.

Most people who are drawn to using ID apps don’t have the ability to confirm that those three points apply. If you are knowledgeable enough to capture all the important identifying features, and to understand and trust the AI’s taxonomic framework – you are probably knowledgeable enough to identify the plant yourself without an app. And AI apps are usually “black boxes” which specifically withhold information about where their data came from or how they were trained, which makes it difficult or impossible to actually judge their reliability.

The universal problem with AI is that it cannot admit when it doesn’t know something. So if you give it a poor-quality photo, show it a plant it’s never seen before, or just don’t realise that the app you’re using was trained on outdated classifications – it will give you a confident and totally incorrect answer.

Here are the suggestions from some popular ID apps when I showed them Tradescantia ‘Raspberry Ruffle’. This cultivar is a previously-undescribed hybrid between the species T. brevifolia and T. hirta, which means that there are no other specimens or photos of plants like it anywhere.

If you showed this plant to a knowledgeable human, they would be able to recognise that it didn’t match any familiar species. They might mention the species it most resembles, but crucially they would be able to consider the possibility that it wasn’t any of those.

In contrast, AI apps always have an answer. One of the apps above gives a percentage confidence rating for its suggestions, which does at least hint that they’re not very reliable IDs. But it still suggests them, and certainly doesn’t offer “No idea” as a possibility. And the percentage ratings are not a particularly useful way to judge the accuracy of the suggestions, because it’s possible for an AI to be very confident about a wrong answer.

Because AI can’t be trusted to admit ignorance, all of its answers should be treated with suspicion. Think of it as an unreliable friend who you know is prone to lying and exaggeration. Plant identification apps (and in fact, all uses of similar AI models) should only ever be the start of the solution. Whatever response an AI gives you, you should never consider it final or authoritative. Treat it only as a suggestion which you might use to direct your own further research in order to confirm or correct it.

How to get a plant identified

There’s a reason that botanists don’t use single-photo ID charts or AI apps for their research. It’s because experienced and knowledgeable humans are by far the most effective and reliable plant identifiers there are. People spend their lives developing those skills because they are both difficult and valuable skills to have.

So if you think you’ve found a shortcut way to identify plants easily, ask yourself some questions:

- Could it tell you if it didn’t know the answer? (For example, if the plant is a brand new hybrid or newly-discovered species)

- Could it tell you if you haven’t provided enough information to identify the plant? (For example, if the plant is not in bloom, but it can only be distinguished from close relatives by flower characteristics)

- Could it tell you if the plant doesn’t belong to the target group? (For example, if the plant is from a different family not covered by the guide or app, or if the specimen is actually a fungus rather than a plant)

- Could it explain how it chose its answer, and how it ruled out other possibilities?

If you can’t trust your source to do those things, then you can’t trust its identifications. That goes for humans too, by the way! Don’t trust an “expert” who can’t explain their answers or admit ignorance.

Anyone can become an experienced and knowledgeable identifier, with time and practise. If you want to get good at identifying tradescantias (or any group of plants), here are my tips:

- Read scientific descriptions of species and cultivars, including both old and new sources.

- Look at photos of correctly-identified plants.

- Grow correctly-identified plants yourself – experiment with different growing conditions, and spend time looking at them carefully.

Remember that “correctly identified” plants means plants identified by a reliable expert human who can explain their answers and admit when they don’t know something. If you base your learning entirely on ID charts and AI apps then your knowledge will be built on flawed foundations.

Do those things as much as possible, for months or years, and eventually you can be one of the expert humans that others rely on!

And if you want to get your plants labelled correctly without having to become an expert just for the sake of a hobby, please step away from the ID charts and apps and just ask for help.

Found this article useful?

If you want more great resources like this, you can help me keep making them with a regular payment on Patreon.