Skip to: Summary // Background // Methods // Results // Limitations // Conclusions

My peer-reviewed research paper, Effect of drainage layers on water retention of potting media in containers, has just been published. The paper is open access (free to read) in PLOS One, and contains all the details of the methods, statistical analysis, and citations. This article is a more reader-friendly explanation of the research and its implications.

Summary

Saturated soil is a common problem for container plants. For a long time, gardeners have often added a layer of coarse material like gravel at the bottom of a pot to improve drainage. But in recent years some experts have claimed that these layers actually raise the saturated water level and make drainage worse.

I did a set of experiments with different potting mixes and drainage layers, to see how much water was retained in containers after saturating and draining. I also calculated estimates for how much water was retained in the soil alone, excluding the drainage layer itself.

My results showed that drainage layers usually do improve drainage, and are very unlikely to make it worse. The drainage layers I tested were more effective with coarser potting mixes, and thicker layers were more effective than thinner ones. Overall a 60mm layer of coarse sand was the most universally-effective type of drainage layer for all the potting mixes I tested.

Background

Saturated soil and excess moisture are undesirable for most plants, but they’re a common problem in container growing. People often recommend putting rocks or gravel above the drainage hole in a plant pot as a way to reduce water retention. But in recent years, it’s become increasingly common to describe this idea as a myth, and to argue that adding drainage layers will actually increase water retention and therefore harm plants.

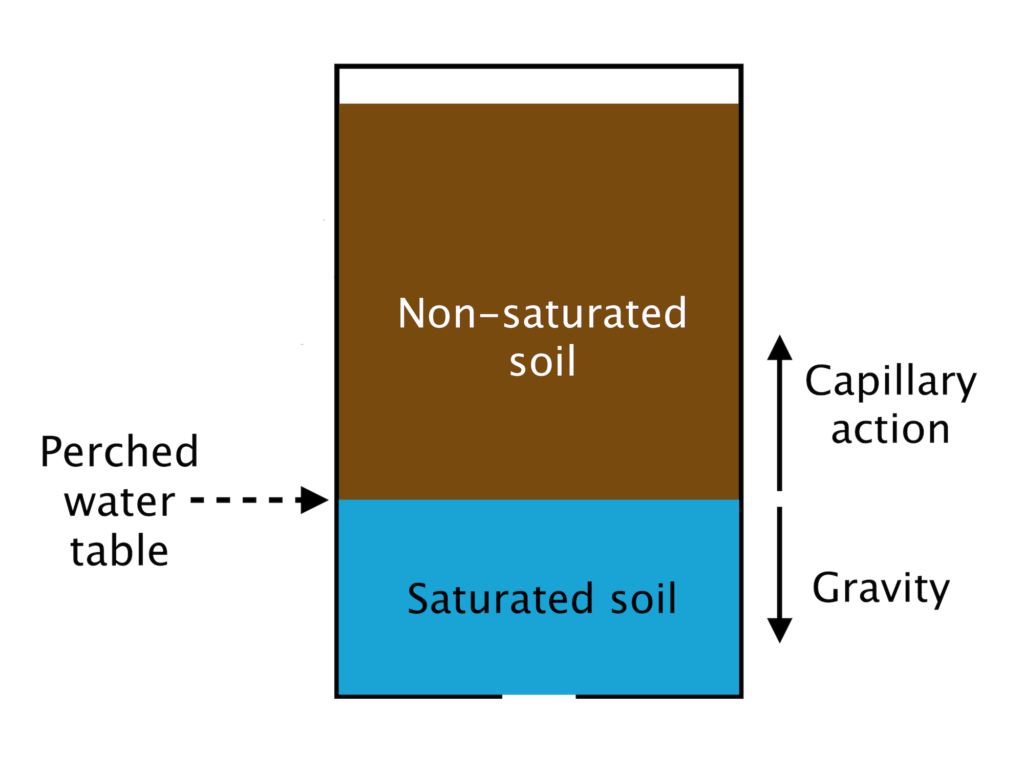

When water is poured into a container of soil, two main forces act on it. Gravity pulls it down towards the bottom of the pot, and capillary action (the wicking force created by absorbent materials like soil) pulls it upwards to spread out through the pot. Water pours out of the drainage hole until the two forces reach a balance. The result is a pool of water saturating the soil near the bottom of the pot. Gravity stops it from being pulled back up and spread out through the rest of the soil, but capillary action stops it from being pulled down and out of the drainage hole. The height that this pool of water reaches inside the container is called the perched water table.

Most of the recent claims that drainage layers are harmful are based on two main arguments:

- The simple logic that adding a layer of gravel below the soil effectively raises the bottom of the container relative to the soil surface, which in turn must raise the perched water table.

- An old piece of research which showed that water flowing downwards won’t cross the interface between two different soil types until the soil above it is almost completely saturated. This suggests that water in a plant pot won’t flow down through the gravel layer until the soil is mostly saturated, which would mean a much higher perched water table.

These two arguments miss out on a lot of the other complex factors involved in water movement. Making theoretical predictions can be helpful, but without experiments to confirm how things really work in practise, those predictions are only so reliable. And since that research in the 1950s, there has been a huge amount of new and more advanced studies about water movement in soil, with a lot that’s relevant to this particular question.

It’s been well-established that a layer of coarse material (like gravel) does act as a barrier to water moving through soil in the ground, with coarser materials having a stronger barrier effect. A mathematical analysis showed that the barrier effect is strongest when the contrast of particle sizes between the soil and the barrier material is infinite. This suggests that soil suspended over air (like a container with soil directly above the drainage hole) will hold onto more moisture than soil over any other material (like a drainage layer of gravel).

Other research on green roofs, artificial containers, and layered substrates have also shown that water movement is a lot more complex than previously thought. A lot of these more recent findings have suggested that adding a drainage layer of gravel may actually reduce the water retained in a container.

But that exact scenario has never been tested directly. Most of the research above was done on field soils from the ground, which can behave very differently from the potting mixes that are usually used for container plants. Water movement is also strongly affected by the size and shape of the container, so research done on large green roofs, out in the ground, or with laboratory boxes and cylinders, might not apply to typical plant pots.

I decided to do a set of experiments to measure how drainage layers affect the water retention in containers of potting mix in a real-world situation.

Methods

I used clear containers with a typical tapered plant pot shape, about 1 litre in size, with a hole in the bottom. I varied several different factors in the experiments:

- Three types of potting mix (ranging from dense loam-based compost to coarse and chunky coir mix),

- Four drainage layer materials (ranging from 4-10mm gravel to 1-2mm sand),

- Two drainage layer depths (30mm and 60mm).

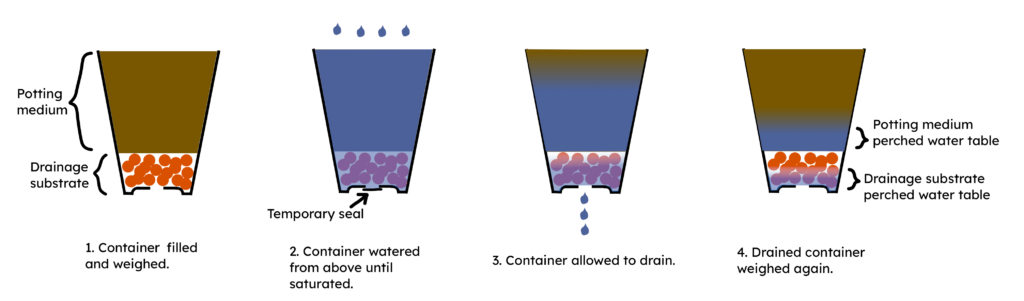

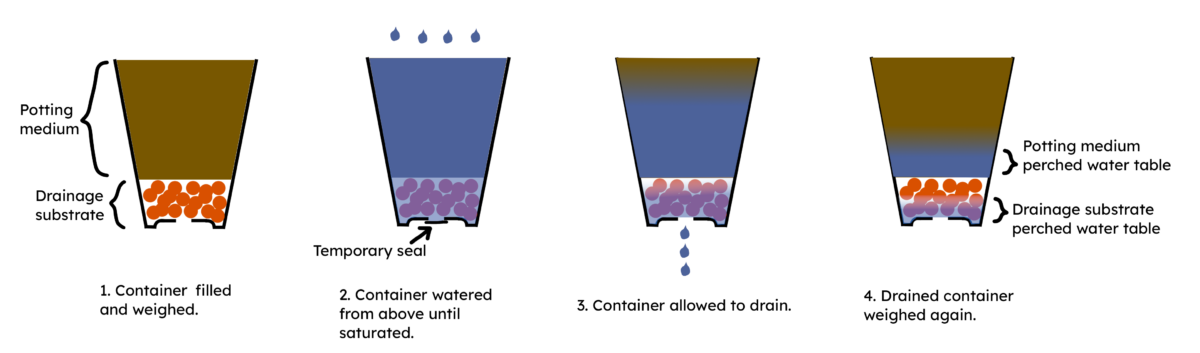

This gave a total of 24 different combinations, and I did ten replications of each to make sure the results weren’t skewed by any random errors. The experimental procedure was simple:

- Fill the container with the drainage layer and potting mix, then weigh it when dry.

- Temporarily seal the drainage hole, fill the container with water to the brim, and weigh it again.

- Unseal the drainage hole to let the water run out.

- Weigh the drained container one last time.

Using the different weight measurements, I calculated how much water was left in the entire pot after being saturated and drained.

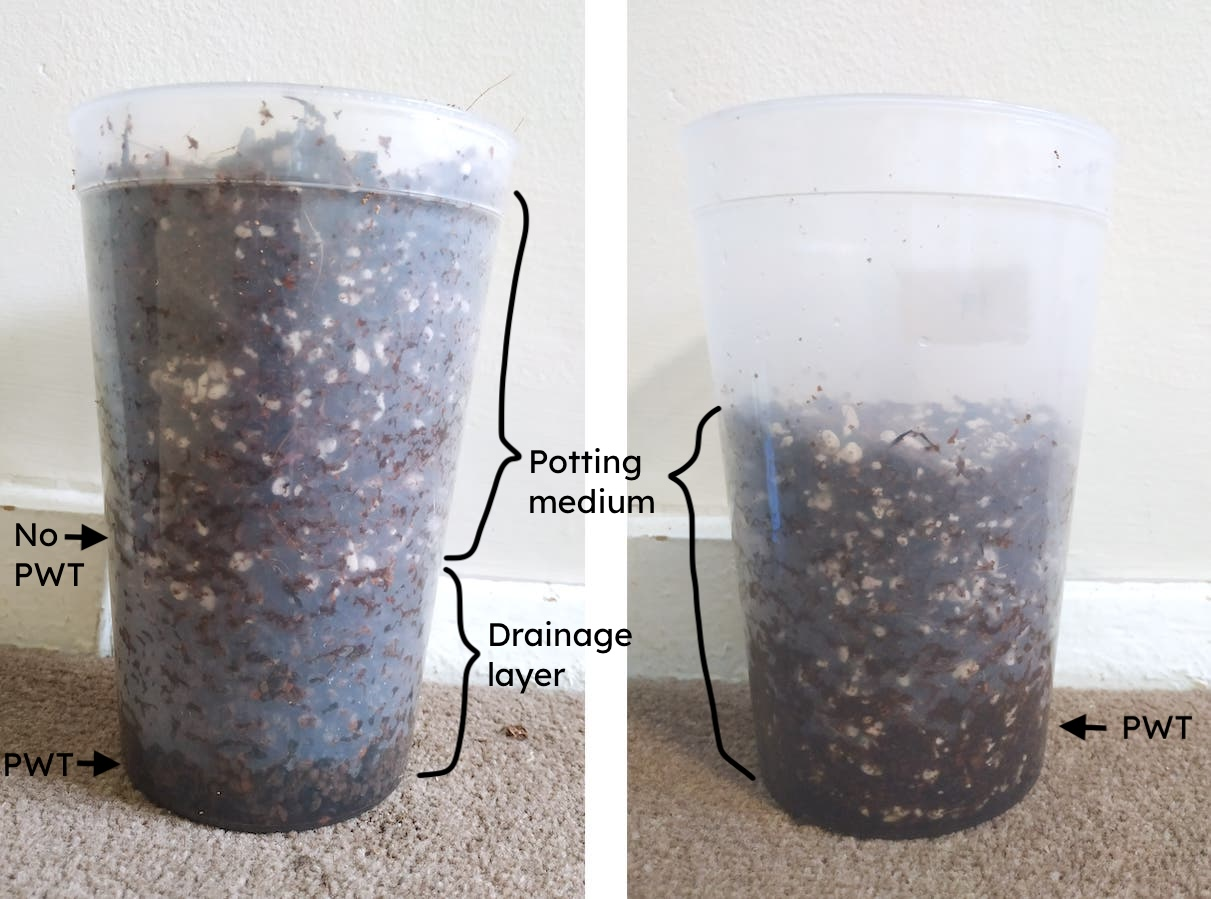

I also used the measurements to calculate two different estimates for how much water was retained in the potting mix alone, excluding the water left in the drainage layer itself. It wasn’t possible to measure this exactly, so the two estimates gave an upper and lower bound for the real values, as a starting point. This made it possible to see how a pot with a drainage layer would compare to an equivalent shallower pot of just soil.

Results

The different types of potting mix were affected by drainage layers differently.

For the chunkiest mix, drainage layers always improved drainage. Every type and thickness of drainage layer reduced the water retained in the container. And both estimates showed that all drainage layers reduced the water retained in the potting mix alone.

For the intermediate mix, drainage layers usually improved drainage for the whole pot, and always improved drainage for the soil itself. Most of the drainage layers reduced the water retained in the container, but some had no effect. Thicker drainage layers were more effective than thinner ones. Both estimates showed that all drainage layers reduced the water retained in the potting mix alone.

For the densest mix, drainage layers usually didn’t affect drainage for the whole pot, but probably improved drainage for the soil itself. Most of the drainage layers had no effect on water retention in the container, but one reduced it, and one increased it. The two estimates gave different predictions for the water retained in the potting mix alone, but from visual observation the most accurate estimate showed that all layers decreased water retention.

Overall, a drainage layer is a useful way to reduce how much water is retained in a plant pot. The results showed that adding a layer of coarse material at the bottom will usually improve drainage, and is very unlikely to make drainage worse. The most universally-effective drainge layer for all the potting mixes in the test was a 60mm layer of 1-2mm sand.

Limitations

In my experiment I directly measured the amount of water retained in the entire container. This included water in the soil and water in the drainage layer itself (which has its own perched water table at the bottom). I also made estimates of how much water was retained in the soil alone, but I couldn’t measure that directly. In some cases, drainage layers didn’t reduce water retention of the whole container, but did seem to reduce water retention in the soil above. More detailed water movement experiments would help to show which of my estimates was more accurate for the water retained in the soil alone.

My experiments were designed simply, with the aim of matching real-world growing conditions. The individual trials were controlled and repeated to make sure the results were valid. But I didn’t do any other laboratory tests on the soil, the containers, or the details of how water moved through the pots during the experiment. Replicating the experiment while studying these factors would help to understand why my experiments got the results they did. And replicating the experiment with different potting mixes, drainage layers, and containers would give more information about what happens in a wider range of different real-world situations.

For my experiments, I fully saturated the containers before draining them, and in my calculations I assumed there were no air bubbles at that point. This made it possible to study drainage without considering what happens when water is added to soil. But it was a simplification which doesn’t completely represent reality. When watering a normal plant pot from above, water actually starts to drain out of it before the soil is fully saturated. And even when a container is soaked in water, there are still some air bubbles trapped among the soil. Recent research has shown that the water content of soil changes depending on whether and how the water is moving, in ways which aren’t fully understood yet. All of this means that a lot more study is needed to explain what the results of my experiments really mean.

I also didn’t test how living plants reacted to growing in containers with drainage layers. Although my results showed how to improve drainage of a container, they can’t predict whether a plant will actually benefit from that. Recent studies of plants grown with a more coarse layer of mix in the bottom half of the pot found that they often had better quality and crop growth. But more controlled trials would be needed to see whether different plants grow better in containers with shallow drainage layers, like home gardeners often use.

Conclusions

The predictions which lead people to think drainage layers are harmful are based on a simplified and fairly outdated understanding of water movement through soil. It’s true that an interface between soil and gravel (as at a drainage layer) is a barrier to water movement. But an interface between soil and air (as at the bottom of the pot) is an even greater barrier. So adding a layer of gravel in between provides an easier route for the water to drain out. This in turn reduces the perched water table in the soil above.

My results showed that the idea of drainage layers being a myth, is itself a myth. In fact, the old practise of drainage layers really is effective.

Found this article useful?

If you want more great resources like this, you can help me keep making them with a regular payment on Patreon.

9 replies on “The myth of the myth of drainage layers in containers”

How do you suppose drainage layers within ‘no drainage’ containers e.g. glass mason jars affect the water retention in the potting medium? Would it still create a PWT below the soil and /or within the drainage layer?

I note your drainage layers contained quite small media- would something larger like LECA balls have a detrimental effect or would their wicking capabilities support both a PWT and free upward movement of water from the saturation point throughout the potting media?

I didn’t study that situation, but I assume the result would be mostly the same. The main issue with no-drainage containers is that if a lot of water is added at once, it can fill up and full saturate the drainage layer (and more). But with only a small amount of water, it run through the soil, leaving behind a PWT at the boundary, and then pool at the bottom of the drainage layer.

Good question about larger drainage substrates. If we try to extrapolate from the results of the research, I would predict that larger particle sizes would be decreasingly effective. In the experiment, the smallest particle sizes generally had the most drainage effect, and that’s consistent with theoretical predictions that a bigger particle size contrast between the two materials leads to a greater barrier effect at the boundary between them.

Very interesting. Was there any separation between the layers (lanscape cloth, etc)? For years I have been adding a square of toilet or facial tissue across the drain holes before filling pots with soil with the idea that the tissue not only keeps the dirt in, but also pulls excess water down and out. Now I feel encouraged to experiment and find out if this is actually the case!

The talk of perched water tables reminded me of the pot-in-pot method for lowering the PWT from a successful hibiscus grower: https://internationalhibiscussociety.org/homes/competitions/growing-hibiscus-in-pots I’ve used it with outdoor plants so that I can water them for vacation without soggy roots.

Thanks for another interesting article!

I’ve (unscientifically) experimented with using cotton twine, running out the bottom into the dish below, with a similar idea of encouraging wicking. I wonder if that disrupts the water table in a helpful or harmful way. But the tissue idea maybe answers my question of how to keep a sand layer from running out the bottom!

Amazingly helpful article, thanks!

Thank you for this very interesting discussion. I would like to introduce it in Japan.

In Japan, 1–2 cm pumice stones are commonly used as drainage material. When a layer of pumice of this size is placed at the bottom (for example, if a 4 cm layer is added, the upper 2 cm or so becomes a mixed zone), the potting mix collapses into the large gaps and the two materials form an interlocking, blended layer. Because this makes the water movement more complex, I’m not sure we can necessarily say that a larger difference in particle size always leads to poorer drainage efficiency. What do you think?

When I tested this using a transparent pot, water flowed quickly through the easier pathways in the potting mix and drainage began almost immediately. None of the layers became saturated, and it was difficult to observe any distinct layer that could be called a PWT.

Thanks again for sharing your work.

That’s a good question, and I don’t have an answer for it! Intuitively I agree with you, if the two media are able to mix together at the boundary then I think that would probably reduce the capillary barrier between them. But it’s another complex situation that would need to be tested empirically to know exactly what effect it has on water movement in reality.

Yes! And I’m really realizing how hard it is to examine complexity, especially when I’m trying to challenge someone’s argument for not having enough of it…

I have just two more things I’d like to ask.

First, about your paper: the sand you used as a drainage material seems so fine, even by your standards. Is there a particular reason for that? (apologies if you’ve already explained it somewhere.) I ask because many people seem to use larger materials, like bark or broken pots, for the same purpose.

Second, I’d love to hear your thoughts on other people’s opinions. You briefly mention the H&G 1959 experiment in the introduction of your paper. I feel it’s quite unrealistic as a representation of actual soils ,extremely uniform fine soil, and very slow, prolonged wetting, etc. I suppose the extreme setup was intended to make the capillary barrier easier to observe.

I plan to discuss it critically, but many people who cite this theory, including university extension materials, don’t seem to question it at all. Do you think there’s anything important I might be overlooking?

Sorry for the long comment, I’d love to hear what you think!

The sand in my test was 1-2mm which is fairly coarse – most technical definitions say that anything with particles larger than around 0.05mm is sand! But I also tested substrates with bigger particles sizes, up to around 10mm. I just wanted to test a range of sizes to see what differences I would find between them.

I don’t think you’re overlooking anything about H&G’s research, and I agree with you that it’s very limited and doesn’t have much useful application in this question! I only cited it because so many other resources cite it today, even though there are many more modern and more relevant papers we can refer to now (which I also included in my research).

I actually had some quite heated discussions with a group of US extension professors about this both before and after I published my research – I wrote about those interactions in another article you might be interested in: https://tradescantia.uk/article/garden-professors.

Thanks very much for taking the time to reply! Your clarification on both points was very helpful. I asked about the first one only because some of my readers might raise the question, and I wanted to be sure I understood your reasoning.

(I also realize I haven’t read the newer studies you referenced in your paper, so I’ll need to take a look at them.)

I had already read your discussion with the Garden Professors. It’s clear that stepping into that kind of discussion takes both courage and a lot of emotional energy! I appreciate your openness and the care you put into responding.