Tradescantia ‘Nanouk’ and Tradescantia ‘Lilac’ are particularly trendy cultivars with thick stems and tough, pink-striped leaves. But there’s a lot of controversy and arguments about the plants’ status and identity. ‘Nanouk’ is often described as stolen, fraudulent, or a scam. People say that ‘Nanouk’ doesn’t truly exist, and is just ‘Lilac’ disguised with plant growth regulators.

I came across some of these claims, and found that it was really difficult to get to their origins or supporting evidence – they get passed around a lot as secondhand information without sources. I don’t like sharing information without checking the facts myself, and I wanted to figure out the real origin and truth of the claims, so I did my favourite thing: a ton of obsessive research.

The first part of this article is a summary of the claims I’ve come across and whether they are true, false, or unknown. The second part is a thorough write-up of all the sources and evidence I used, so that anyone who is sufficiently interested can confirm it all (or dispute my conclusions with evidence). At the end are some appendices with basic information about some of the jargon to provide extra context and details for anyone who needs it. There are anchor links throughout the article to make it easier to navigate between sections. (Tip: in most browsers if you click an anchor link and then click ‘back’, you’ll be conveniently returned to your previous spot on the page.)

The Facts

The overall claim

| Claim | Truth | |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Nanouk’ was patented fraudulently, in a deliberate attempt to steal ‘Lilac’ | There is no evidence that ‘Nanouk’ is fraudulent or stolen |

This main story seems to have arisen from a few specific and fairly innocuous facts, and then been expanded to include much more serious and unsourced accusations. From the evidence, the overall conclusion is that there is no sign of illegal or particularly unethical activity from anyone involved.

The overall claim is made up of many separate small pieces of information, some of them true and some false. So first I’ll cover the individual aspects, and then come back to how the overall conclusion follows.

The individual claims

| Claim | Truth | |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Nanouk’ is patentedinfo | ‘Nanouk’ is patented in the USA and legally protected in the EU |

There is an active US patent for Tradescantia ‘Nanouk’. It was filed in 2017, granted in 2018, and expires in 2037.source

Under the plant breeder’s rights system in the EU (not patents but a similar form of intellectual property), there is an active registration for Tradescantia ‘Nanouk’. It was first applied for in 2014, published in 2018, and expires in 2043.source

| Claim | Truth | |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Lilac’ was patented first | There has never been any US patent or EU protection for ‘Lilac’ |

A patent is by definition a public legal document. The USA has an online database of all patents, and there is no active or expired patent for Tradescantia ‘Lilac’.source

The EU plant breeder’s rights database is similarly public, and there is no active or expired registration for Tradescantia ‘Lilac’.source

| Claim | Truth | |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Nanouk’ and ‘Lilac’ are the same plant | They seem to be indistinguishable, so they can be considered the same cultivar |

‘Lilac’ and ‘Nanouk’ seem to be indistinguishable. Lots of people who have bought both plants say that they seem to be the same.source

Neither the original ‘Lilac’ producers nor the ‘Nanouk’ breeder have made any claims about the cultivars being related or the same – in fact the ‘Lilac’ producers don’t know anything about ‘Nanouk’.source The original ‘Lilac’ was sold between 2013 and 2016.source The ‘Nanouk’ patent says that it was created in a breeding program in 2012,source and the first official record of it was from 2014.source So it’s now difficult to know the origin of any plants currently in circulation, but it seems that the cultivars could have arisen separately at around the same time.

Unless the original producers of both cultivars decide to submit samples of their original stock to a willing lab for molecular testing, it’s impossible to know whether or not they are genetically identical. For the purposes of cultivar definitions, if two plants are indistinguishable they should be considered the same regardless of their origins. According to the rules of cultivar naming, the oldest name takes precedence unless one of the names has been registered for a patent or plant breeders rights.info As we determined above, ‘Nanouk’ is patented and ‘Lilac’ is not, so the correct name for this cultivar is ‘Nanouk’.

| Claim | Truth | |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Nanouk’ is treated with plant growth regulators (PGRs)info | Some growers treat ‘Nanouk’ with PGRs |

The current owner of ‘Nanouk’ has acknowledged that it is sometimes treated with PGRs before sale, which is a common practice in the ornamental plant industry.source Treated plants will generally have smaller and rounder leaves, and once the PGRs wear off the leaves become larger and longer.

| Claim | Truth | |

|---|---|---|

| The ‘Nanouk’ US patent is invalid because it contains incorrect information | There are two incorrect pieces of information in the patent, but this doesn’t invalidate the patent |

The first piece of incorrect information is the scientific name for the plant.info In both the patent and the EU plant breeder’s rights, the name is given as Tradescantia albiflora. This species no longer exists, and has been considered a botanical synonym for Tradescantia fluminensis since at least 2004,source long before either cultivar was produced.

In fact ‘Nanouk’ is not T. fluminensis at all – its flowers and growth habit show that it belongs to a related species, Tradescantia cerinthoides. Many cultivated Tradescantia plants are labelled as T. albiflora when they actually belong to other species in the same subgenus.source This kind of misnaming is very common in horticulture.

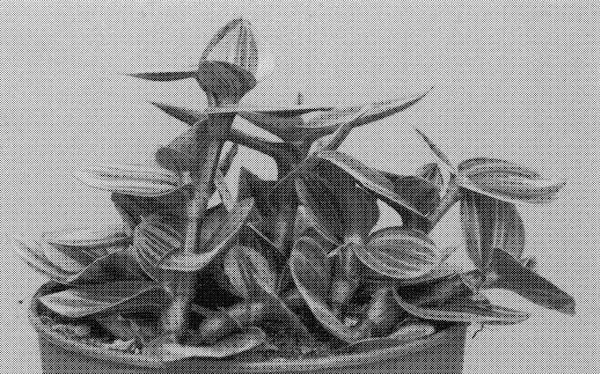

The second piece of incorrect information is the leaf size. The patent describes the leaves as about 4.2cm long and 2.8cm wide.source Most people who have bought ‘Nanouk’ plants agree that the leaves soon grow bigger than this.source It also conflicts with the information in the EU plant breeder’s rights registration, which describes the leaves as 12cm long and 5cm wide.source The owners of ‘Nanouk’ have said the size in the US patent describes the plant when grown under professional conditions, including appropriate use of PGRs.source

US plant patents specifically protect the genetics of a single plant.source The incorrect details in the description are strange, but they don’t make the patent invalid or fraudulent. The plant itself is still protected because it has the same genes.

The overall conclusion

Some of the claims people make about ‘Nanouk’ are clearly true.

- It has a US patent, which anyone can find online through a quick search.

- It’s often treated with PGRs like many cultivated plants, so its growth habit will sometimes change noticeably over the first few months after buying it.

- The plant is indistinguishable from ‘Lilac’, and they can be considered the same cultivar.

- It’s a different species from the T. fluminensis (synonym T. albiflora) that it’s often sold as.

Individually, those facts are all the product of very normal and common occurrences.

- Plant patents are a recognised form of intellectual property in the USA.

- Many cultivated plants are treated with PGRs during production.

- There are countless similar-looking plant cultivars throughout the world of horticulture, and countless cultivars which end up sold under multiple names.

- Growers often use outdated or incorrect botanical nomenclature for cultivated plants because they are not closely associated with the scientists studying wild species.

But the more negative and extreme claims being passed around are largely false.

‘Lilac’ was never patented, and so ‘Nanouk’ could not possibly be defrauding it. No one actually associated with either cultivar has made any allegations of fraud, never mind taken legal action (which would certainly be affordable for the huge multinational businesses involved). The only evidence to suggest the two originated from the same plant, is that they look similar. This is true of many cultivated plants, because there is no strict regulation of cultivars if they aren’t legally protected. And even if the two cultivars are genetically identical (which is a possibility – it’s almost unprovable either way), all that means is that one large business made a smart choice to take over a product when another large business gave up on it. Which is a pretty everyday event in the world of capitalism, whether you approve of that or not.

As plant nerds and enthusiasts (which I can confidently assume we all are, if you’re reading this), some of those things might seem unfair or immoral. But the truth is that different people just have different priorities and different sources of information, and sometimes those things clash and people can end up confused or disappointed. That doesn’t mean that anyone involved is evil or criminal – just that they are doing things differently. There is no underdog in this situation, no hardworking individual who carefully bred a plant and had it ruthlessly stolen from them. There are just two big businesses, doing big business things, and neither of them actually knows or cares about this controversy – because as far as they’re concerned, there is no controversy at all.

The Sources

In this section, I’ll give the sources for all my information and explain how I drew the conclusions I did. My goal with this article is to correct misinformation in a way that anyone else can confirm for themselves.

When I started researching this subject I kept coming across people referring to other people referring to other people, and no one referring to any kind of objective evidence. And when I did try to figure out why these secondhand stories were considered reliable, it seemed to just be that the people spreading them had a lot of influence. Popularity and credentials are great, but they don’t verify claims – evidence does. So if you don’t like me or don’t know me well enough to trust what I’m saying, you should be able to read through my sources here and come to the same conclusions independently.

Plants of the World Online

This is the source I referred to for the most up-to-date information about plant taxonomy.info It’s an online database which contains entries for every known plant species in the world, hosted by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. The relevant part for the purpose of this article is the entry on Tradescantia albiflora, which describes it as a synonym for T. fluminensis with the earliest reference from 2004. This means that scientists consider those two names to refer to the same species, and the name T. fluminensis takes precedence.

To learn more about how plant names work in general, check out this article too!

Taxonomic revision of Tradescantia subgenus Austrotradescantia

This is a scientific paper from 2018 by Marco Pellegrini, which gives detailed accounts of the currently accepted species in a particular subgenus of Tradescantia – Wandering throughout South America: Taxonomic revision of Tradescantia subg. Austrotradescantia (D.R.Hunt) M.Pell. (Commelinaceae).

The paper describes T. albiflora as a synonym of T. fluminensis. But it also explains that there are many plants in cultivation labelled as T. albiflora which actually belong to other species in the subgenus – such as T. cerinthoides.

This type of mislabelling is very common in horticulture.info Taxonomy is focused on wild species as they occur naturally. But cultivated plants are generally selectively bred, randomly mutated, and sometimes hybridised between species. It is often impossible to know the exact wild ancestors of a cultivated plant, and growers generally don’t care about that anyway. They are focused on producing popular and attractive plants, and the names they use only need to serve the practical purpose of being recognisable and useful. In the case of this subgenus, it’s become commonplace to use the name Tradescantia albiflora to refer to many different species, and that categorisation is useful to growers – even if it doesn’t match the categorisation that taxonomists use for wild plants.

‘Nanouk’ US Patent

This is probably the easiest evidence to find, because a patent is by definition public.info There’s a copy hosted by google which comes up first if you search for “nanouk patent”, but for the sake of credibility it’s also available from the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) online database. The website and search are not particularly user-friendly, but here is a direct link to the full patent document for TRADESCANTIA PLANT NAMED ‘NANOUK’ PP29,711 P2.

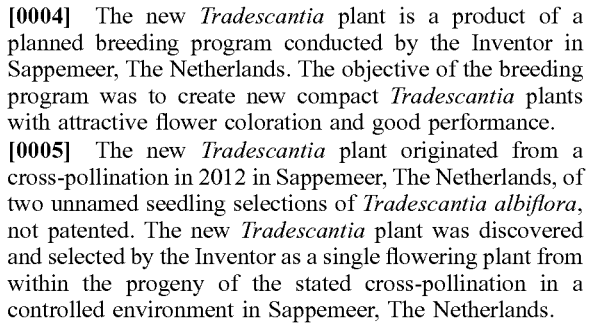

The applicant and ‘inventor’ of the plant is named as Wander Durk Tuinier, and the assignee (the current owner) is Dummen Group B.V. (Dümmen Orange – a large multinational plant breeding corporation). The patent was filed on the 28th March 2017, and granted on the 25th September 2018. It describes a T. albiflora plant which arose from a planned breeding program in the Netherlands in 2012.

The leaves are described as light purple, green, and greyed-green striped, about 4.2cm long and about 2.8cm wide. There are also greyscale scans of photos showing the stems and leaves.

‘Nanouk’ EU Plant Breeder’s Rights

The Community Plant Variety Office (CPVO) hosts an online database for plant cultivars protected in the EU, and with a search for application number 20161903, you can find the entry for Tradescantia ‘Nanouk’.

It confirms that ‘Nanouk’ is registered for plant breeder’s rights in the EU. The breeder is named as Succulents Innovations B.V. (Wander Tuinier’s company at the time of application – the same as the breeder on the US patent), and the holder (the current owner) is Dümmen Group B.V. (Dümmen Orange, the same international business that owns the US patent). The application was made on the 3rd August 2016, and rights granted on the 23rd April 2018.

The documents associated with the entry also feature a more detailed committee decision document from the organisation that tested the cultivar. This contains some interesting and precise measurements of different parts of the plant when it was tested – most notably the leaf blade length (ca. 12cm) and width (ca. 5cm), which is different from the measurements in the US patent.

Via the same database you can also make a request for even more documents about a particular entry. It took a few weeks for me to get a response because it has to go through an actual human, but there don’t seem to be any restrictions on who can request documents or why. The full, original application form is accessible this way. It includes some colour photos of the plant dated May 2014, lots of boring administrative forms, and a few interesting extras.

One interesting part is the applicant’s description of the origin of the plant as a chance seedling, which matches the claims in the US patent.

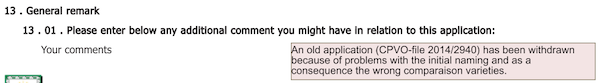

There’s also a note about an earlier application which was withdrawn because of a naming issue.

This withdrawn application can also be found in the database as number 20142940. The application was made by Wander Tuinier on 14th November 2014, and then withdrawn on 19th July 2016. There’s no additional information because the application didn’t go through, but it proves that Wander Tuinier had the ‘Nanouk’ cultivar as early as 2014 – which lends weight to the claim that it was first bred in 2012, before ‘Lilac’ was sold.

‘Lilac’ Patent Search

Not the most thrilling evidence, but important to include: the USPTO patent search results for “tradescantia AND lilac”. There are twelve results, none of them referring to the Tradescantia ‘Lilac’ plant in question. Other searches for “tradescantia” or “lilac” are similarly fruitless. There is no patent.

‘Lilac’ EU Plant Breeder’s Rights Search

As above, a search of the public CPVO database for Tradescantia ‘Lilac’ gets no results. Searching individually for all Tradescantia varieties or all varieties named ‘Lilac’ also turns up nothing.

Athena Brazil Catalogues

Athena Brazil is a large international plant breeding company, and the original producer of ‘Lilac’. The first evidence of them selling it is from their 2013/2014 catalogue. On page 55 there is a photo of a pink and green striped plant with pink flower buds, labelled as Tradescantia fluminensis ‘Lilac’.

It’s also in the 2014/2015 catalogue on page 48, and in the 2016/2017 catalogue on page 22, but it’s not in the 2017/2018 catalogue. So we can assume they stopped selling it sometime in 2016.

Athena Brazil Emails

I emailed Athena Brazil’s customer service to ask whether the ‘Nanouk’ patent is what forced them to stop selling ‘Lilac’. I got a brief response apologising for not knowing anything about ‘Nanouk’ – which was in itself very informative.

I have no information on this ‘Nanouk’ variety, we don’t even have this variety anymore and we just stopped selling because it was not interested in the market itself. I’m sorry I can’t help you more, but that’s all I know about it.

They don’t know anything about ‘Nanouk’ – they just dropped ‘Lilac’ because it didn’t sell well.

Dümmen Orange Catalogue

Dümmen Orange is a large international business that currently owns the rights to produce and sell ‘Nanouk’. It features on page 39 of their 2020/2021 catalogue. There are photos and descriptions of the plant, and one of the selling points given is that it responds well to PGRs.info There’s certainly no attempt to conceal the fact that PGRs are sometimes used.

Dümmen Orange Emails

I emailed Wander Tuinier, the original breeder of ‘Nanouk’, to ask some questions. They forwarded my questions straight onto Dümmen Orange as the current patent owner – it was clear Wander Tuinier was not willing or able to discuss it personally.

My first question was whether ‘Nanouk’ was actually T. fluminensis, or whether it was a hybrid with T. cerinthoides. They said they couldn’t reveal their breeding secrets but called it a product of multiple complex interspecific crosses.

As a professional breeding company we will not relay any specific details on the genetic background of our commercial varieties and seedling selections.

However I can inform you – as a plant lover – that Tradescantia Nanouk is derived from multiple complex interspecific crosses.

This didn’t really tell me anything new, because it didn’t address the confusion over scientific names.info What they call “interspecific” (i.e. “within the species”) could have just meant “within everything horticulturalists call Tradescantia albiflora“, which really means anything in the subgenus Austrotradescantia – including both T. fluminensis and T. cerinthoides (among others).

I then asked why there was a discrepancy in the leaf sizes described in the US patent and the EU registration – were they actually different varieties? The response was very clear: they’re the same cultivar, but the leaves are just smaller when treated with PGRs.

The variety sold in USA is the same as the one sold in Europe.

When grown under ‘professional’ conditions, including the use of appropriate plant growth regulators, the appearance of Tradescantia Nanouk is more similar to the US PP description.

Patent Agent Emails

I got in touch with a specialist patent agent in the USA, who kindly gave some very detailed answers to my excessively detailed questions. The most helpful point was their explanation that a plant patent refers very specifically to the genetics of one single plant. The description in the patent is for convenience only, but the thing that’s really being protected is the genes.

A Plant Patent is unique in that only one “claim” is allowed which is always, as a requirement, direct to the new plant (i.e. 100% of the genome of one individual plant). This single claim requirement dictates the scope of a US Plant Patent. As an aside, this is why there is an asexual propagation requirement for Plant Patents; because you are essentially cloning the claimed plant to maintain 100% of the same genome.

To really pin this down, I followed up with some hypothetical questions.

If someone grew out a patented plant so that it no longer exactly fitted the description in the patent, is it still legally protected? Yes.

If you knowingly propagated a plant that is patented, and marked as such, then you are infringing upon the patentee’s rights. I would ‘guess’ that arguing that the morphological characteristics of the plant you so propagating did not match what is disclosed in the patent would not be a winning strategy if the complainant (patent owner) could prove where you obtained the plant and that it was, in fact, their patented plant… regardless of how it looked.

If someone bred a new plant that was genetically different but actually did consistently fit the description of the patent, would it be protected by the original patent? No.

If you found a mutation/sport from their patent plant (whether a branch mutation or a whole plant mutation) or if you were to initiate a breeding program using their patented plant as one of the parents (i.e. as either the seed or pollen parent) then you can certainly patent the resulting plant.

It’s clearly a bit strange that the description in the patent doesn’t match the natural appearance of the protected plant. But the patent itself really protects the genetics of the ‘Nanouk’ plant, and the incorrectly described leaf size is an inconvenience, not fraud.

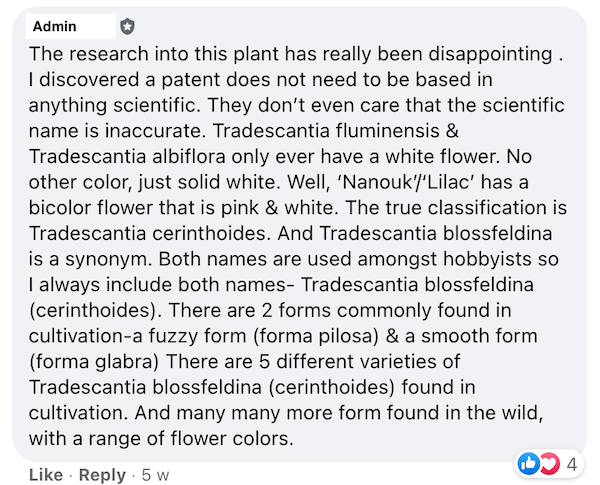

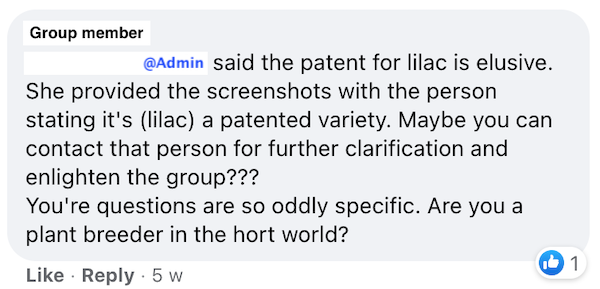

Facebook Group

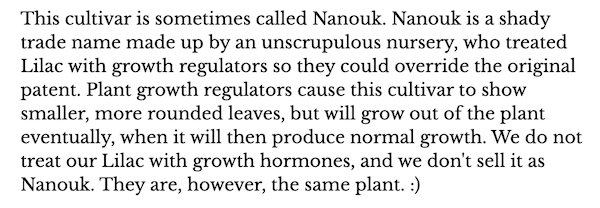

I first came across this whole topic when I saw an online plant shop selling Tradescantia ‘Lilac’. On the item listing, they had a note saying that it was sometimes wrongly labelled as ‘Nanouk’, but that name was false.

They didn’t mention the source of the information, so I emailed them to ask, and they directed me to a facebook group.

When I asked for information in the group, I was quickly given lots of passionate explanations of the fraud and theft story. It’s been very well-established in the group and is accepted as fact to teach to any new members who ask about ‘Nanouk’ or ‘Lilac’. When I asked again for evidence, members jumped in to defend the experience and expertise of the admin who’s considered the authority on the subject.

Some members were so suspicious that I would even ask these questions, instead of simply trusting the admin, that I was accused of working for Dümmen Orange.

In contrast, the admin wasn’t offended, and kindly showed me all the evidence they had collected to prove that ‘Nanouk’ was stolen.

First, there were pictures and catalogues from Athena Brazil showing ‘Lilac’ in 2013 – nothing new there. They explained how many people have found that ‘Nanouk’ plants grow out of their PGR-induced shape and get bigger over time. They described the features that suggest both cultivars are actually T. cerinthoides or hybrids, as opposed to T. fluminensis. And they talked about how many growers have found ‘Lilac’ and ‘Nanouk’ to be similar or indistinguishable.

All perfectly solid evidence for the parts that are true: ‘Lilac’ did exist in 2013, ‘Nanouk’ is often treated with PGRs, they both may be a different species than they’re usually labelled as, and they are clearly similar to one another. None of it is evidence for the dramatic overarching claim that ‘Nanouk’ is stolen and fraudulent.

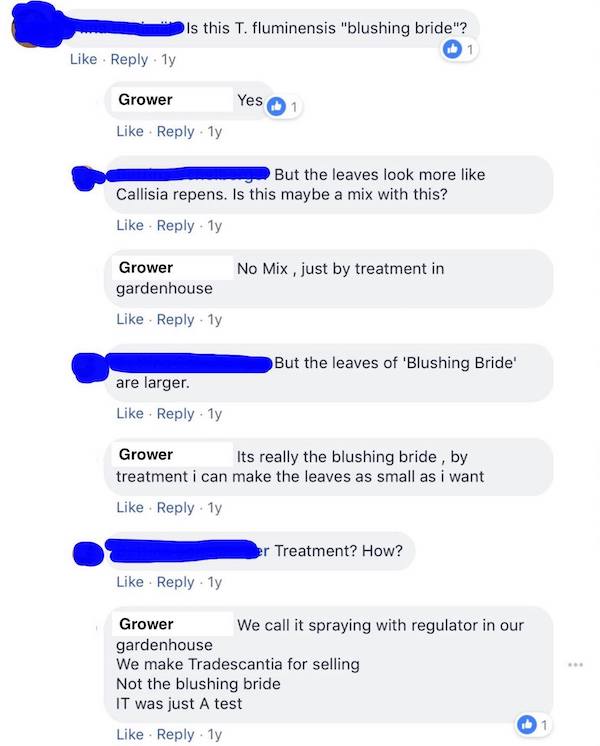

The justification for that turned out to be from a conversation with a particular grower working in a greenhouse that is (or at least was at the time) contracted exclusively to produce ‘Nanouk’ for Dümmen Orange. The admin showed me some screenshots of this grower saying that they used PGRs on another Tradescantia cultivar they produce (the blue was added by the admin to their original screenshot, to cover the name of a group member).

Still no story here, lots of growers use PGRs on lots of plants, and it’s not fraud.

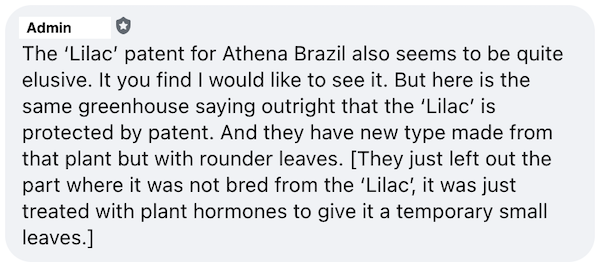

The admin acknowledges that the all-important ‘Lilac’ patent is elusive, and refers to the evidence they do have to show that it’s patented.

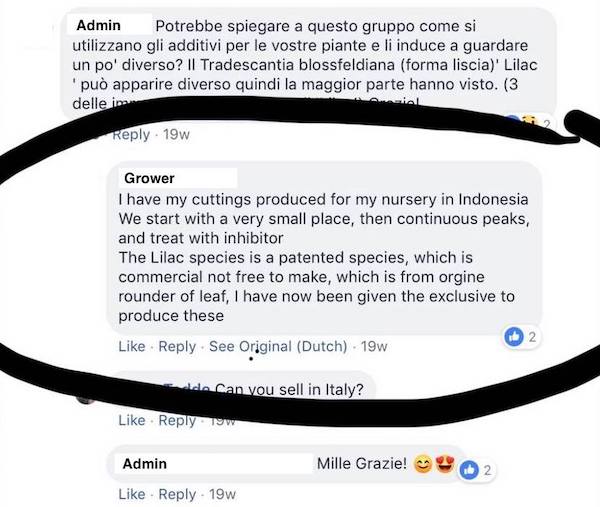

Finally I get to the central piece of evidence – what the group considers to be the proof that ‘Lilac’ was patented first and ‘Nanouk’ was stolen to commit fraud.

It’s a screenshot of a facebook comment from the grower, which has been auto-translated from Dutch. In an untranslated comment in Italian, the admin asks about the similarity to ‘Lilac’. The grower’s auto-translated response was circled in the admin’s original screenshot.

This grower did not provide a patent document or a link to information about it. They didn’t specify who patented it, where, or when. They didn’t make any mention of using ‘Lilac’ to produce ‘Nanouk’, and in fact they made no mention of ‘Nanouk’ at all.

The grammar and organisation of the phrases are very unclear from the translation, but the most logical interpretation I can make is that the grower simply misspoke – and they actually meant to say that ‘Nanouk’ is the one that’s patented, that’s meant to have rounder leaves, and that they had exclusive rights to produce. If that isn’t what they meant, then the comment makes no sense at all, because ‘Lilac’ was never patented and this grower wasn’t producing it.

I will reiterate. This is a screenshot of a facebook comment, which was written in Dutch, auto-translated to English, in response to a question in Italian. It contains no allegations of fraud or evidence of wrongdoing. It came from someone who works in a greenhouse propagating plants, who has no involvement with breeding, patents, or either of the big businesses in the situation. At best, all the comment does is give easily-established facts about ‘Nanouk’ but written with a confusing typo. At worst, it contains clearly false information and nonsense. This is the incontrovertible evidence used to justify the claim that ‘Nanouk’ is stolen.

When I tried to point out how weak this evidence was, another group member suggested I talk to the grower directly.

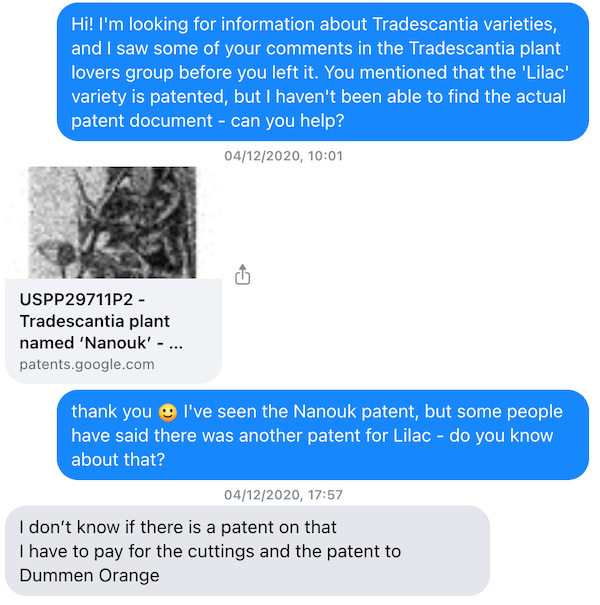

‘Nanouk’ grower messages

So I did.

I messaged the grower referred to in the facebook group, to ask them for clarification. It seemed that no one else in the group had done so in the years since the story developed.

I asked if they had a link to the ‘Lilac’ patent that they’d previously mentioned. They sent me a link to the ‘Nanouk’ patent. I clarified again that I had seen that and I was looking for the ‘Lilac’ patent.

They don’t know anything about a ‘Lilac’ patent. They just pay Dümmen Orange for the right to produce their patented ‘Nanouk’ plants. This is the person used as the source of the entire story that ‘Lilac’ is patented, confirming that they don’t know anything about it.

Appendices

Taxonomy

Taxonomy is the science of categorising and classifying organisms into species and other groups. Taxonomy is almost always focused exclusively on wild organisms as they occur naturally.

A species is a group of related organisms. In simple terms, a species is the way that scientists categorise organisms as being “the same kind of thing”. The exact way that’s defined can vary – for example, scientists might use genetic sequencing, or specific physical characteristics, or analyse which individuals can reproduce together. Species categories are constantly being updated, with the goal of having the most accurate groupings for all scientists to agree on.

A genus is a group of related species. If you think of each species as a person, then a genus is a collection of people who are all siblings. The way scientists define a genus varies, just like for species. Some species within a genus might be grouped into another category called a subgenus if they are more similar to each other than their other siblings.

Every species has a scientific name or binomial name which comes in two parts, for example Tradescantia fluminensis. The first part is the name of the genus, and the second part is the species itself. Both parts of the name are always given, otherwise it’s not clear which organism is being described – just like a person’s full name is necessary to identify them for sure. The first part (the genus) can be abbreviated to its first initial when the full version is already obvious from context, for example T. fluminensis.

Cultivated plants are usually selectively bred, often hybrids, and sometimes mutated – so it might be difficult or impossible to identify their wild ancestor species. Plant growers generally do use species to describe their plants, because it’s useful to have recognisable labels. But those species names don’t necessarily have a close correspondence to the wild taxonomy that scientists use. Growers often use old names, or group many related species into the same name, or use a less-precise genus name only.

You can read more about the systems and rules for naming plants in this in-depth article.

Horticulture

Horticulture is the science of cultivating plants intentionally, usually for particular goals like for food, raw materials, or decoration.

A cultivar is a type of cultivated plant with specific characteristics. Sometimes it’s a group of closely related plants which are propagated by pollination and seeds. Other times it’s a single genetic individual, propagated only by cuttings. The name can be one or multiple words, but is always written in single quotes to distinguish from scientific names, and with the genus or species written first to specify the type of plant – for example Tradescantia ‘Nanouk’.

Cultivars are usually created in artificial conditions – either deliberately through selective breeding, or by chance as mutations. They are ultimately categories that are made up by people because they’re useful, not independent genetic groups that exist without human intervention. For the purposes of defining cultivars, if two plants are indistinguishable, they are considered the same – regardless of their genetic relationship or their origins. Each cultivar only has one true accepted name, which is usually whichever name was published first. But there are several exceptions to that rule. The most significant one for this article is that if a cultivar has been patented or registered for plant breeders’ rights, the registered name takes priority even if it wasn’t the first to be published.

You can read more about the systems and rules for naming plants in this in-depth article.

Plant patents

A patent is a way for a person to claim ownership of an invention and exclude other people from making or selling it, in exchange for providing a public description of the invention. The public description has to be detailed enough to allow someone else to make the invention after reading it. That’s necessary to document what the invention actually is, so that if someone infringes the patent (makes or sells your invention without permission) you can prove that the thing they’re making is indeed the thing you invented and patented in the first place.

A plant patent is a patent that refers to a specific cultivar. Most countries actually don’t allow plants to be patented, but the USA does. The grower has to provide a description and photos of their plant, but there is no testing done on the plant itself. In the USA they’re managed by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). The patent must still have a description, but it doesn’t work in quite the same way as other patents because a plant can’t be created from scratch. Instead the patent specifically protects the genetics of the plant the owner is claiming, so that other people are not allowed to propagate or sell it themselves.

Most other countries have different systems for protecting plant cultivars. In the EU it’s managed by an organisation called the Community Plant Variety Office (CPVO). Because the system was specifically created for plants (unlike the USA patent system), it’s a lot stricter. In order to apply, growers have to submit not only descriptions and photos, but also actual samples of the live plant. Impartial testers then grow and propagate these samples for several years, to confirm that the cultivar is:

- Distinct (not like any already-protected cultivar),

- Uniform (different individuals of the cultivar are the same as each other), and

- Stable (propagating it produces new individuals the same as the parent).

Plant growth regulators

Plant growth regulators (often shortened to PGRs) are synthetic chemicals applied to plants to affect the way they grow. There are many different types, and they’re widely used in horticulture and agriculture for many different reasons. In the world of commercial ornamental plant growing, it’s quite common to use PGRs to make plants more appealing and marketable – for example by keeping their stems short, making their leaves smaller, making them branch more, or getting them to flower at the right time.

If a plant has been treated with PGRs by the grower, that information is not necessarily made available to the eventual buyer. So people are sometimes surprised or disappointed when their plant starts to grow differently after it comes home (like getting longer stems or fewer branches).

For more information about plant growth regulators, you can check out this detailed FAQ article.

13 replies on “The ‘Nanouk’ controversy”

Fantastic read. Thanks for the redirect from Reddit haha.

Both this and your post about mundula vs fluminensis were very informative.

Thanks, glad you liked it!

An excellent article, you’re a great detective! thanks for clarifying this naming issue.

Thank you, I’m glad you found it useful!

Excellent investigative work. I was wondering how so many suppliers on the mail order websites (ie.: Etsy, Pinterest, etc.) are able to offer cuttings or plants identified as ‘Tradescantia ‘Nanouk’, without violating the patent restrictions on the plant. Do they in each case have to obtain consent from Dűmmen Orange, or is there a way around that requirement?

Thank you!

There is no way around the requirement – the truth is simply that anyone selling ‘Nanouk’ without permission (in countries where the patent or protection applies) is breaking the law, whether they realise it or not. Like other intellectual property laws, it has to be enforced by the owner. So people are basically taking a risk and getting away with it because Dümmen Orange either doesn’t notice, or doesn’t care. But if Dümmen Orange did decide to enforce it, they would almost certainly win.

It’s much like people selling, say, homemade Avengers-themed accessories. It’s certainly against the law, but they might not be penalised because Marvel can’t monitor everything and may not bother to take action on small cases.

Maybe the sheer numbers of abuses make it impossible to litigate.

Absolutely brilliant investigation! I was simply curious about this variety and had no idea about the patent drama, but I ended up here and am delighted to have read your work. Thank you for sharing.

THANK YOU! I seriously thought I was the only one so confused about these too. And suspicious about being sold a Lilac when I paid for a Nanouk. But that was because the leaves were much larger, and more narrow than the photos of Nanouks I saw online. Now I know the ones in the photos were treated with PGRs.

Which is blowing my mind the more I think about it, because as a plant nerd I pay very close attention to leaf shape, size, color, shades of color. You know what I mean. So if PGRs can change the appearance of plants so significantly, just long enough for them to be purchased…it feels like false advertising. It should at least have a sticker on it saying “PRG Treaded”.

I’ve literally wasted hours of my life over the last year trying to research about this silly plant lol. Now I’m wondering about my Burgundy Rubber tree who’s leaves aren’t as dark as all the ones I see online .

At least I know about PRGs now, so thank you.

It is really tricky. I agree, it would be ideal for consumers to be informed that a plant has been PGR treated – maybe most people picking it up un a supermarket wouldn’t know or care what that meant but it would be good to at least make the information available. But to call it false advertising kind of suggests that it’s deliberate or malicious, and in most cases I’m pretty sure it’s not.

I’m glad you found the article helpful though! I was in your position a couple of years ago and there was no conclusive summary I could refer to so I had to research all the primary sources myself. I’m happy to have saved someone else from needing to do that

Excellent article! The citations are great and the writing style is clear and highly readable.

Has the facebook group responded to your very thorough and definitive proof that the nanouk is neither fraudulent nor stolen?

Were there any mea culpas from members of the group or the admin?

Some group members appreciated the correction, and others just dismissed my evidence. The central people who perpetuated the myth never openly retracted it, but did conspicuously stop bringing it up…